This report was commissioned by the Only Animal Theatre as part of an exciting national initiative that was inspired by the work of the Artist’s Brigade Greenhouse project entitled Irresistible Worlds in partnership with the National Arts Centre, The Metcalf Foundation, Mass Culture, Canadian Climate Change & The Only Animal.

Report by Dr. Carolyne Clare, with contributions by Alana Gerecke. Edited by Shannon Cuykendall, May, 2023

Yellow Cedar trees at Greenhouse, photo by Sepehr Samimi

Land Acknowledgement

The Only Animal is grateful to work and play on the unceded ancestral territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, səl̓ílwətaʔɬ and shíshálh First Nations.

Gratitude

The Artist Brigade was made possible by our funders, Vancouver Foundation, Canada Council for the Arts, and City of Vancouver. We are grateful for their shared vision and support.

Table of Content

ARTIST BRIGADE ANALYSIS:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. RECRUITMENT

3. GREENHOUSE

4. FIELD TRIPS AND FIELD TRIP PITCHES

5. COMMISSIONED ART

6. 2022-2023: PITCHES AND ACTIVITIES

ARTIST BRIGADE SURVEYS ANALYSIS

1. RECRUITMENT: APPLICATIONS SUMMARY (228 APPLICANT RESPONSES)

2. RECRUITMENT: APPLICATIONS SUMMARY (ARTIST BRIGADE PARTICIPANTS)

3. FEEDBACK ON GREENHOUSE – SURVEY SUMMARY (57 RESPONSES)

4. FIELD TRIP APPLICATION- SURVEY SUMMARY

5. FIELD TRIP PITCHES – PITCHES SUMMARY

6. POST ARTIST BRIGADE FEEDBACK – SURVEY SUMMARY

7. COMMISSIONED PITCHES 2022-23

GREENHOUSE WORKSHOP WORD TREES

COMMISSIONED ARTIST PROFILES

MOHAMMED ZAQUOT

WEN WEN (CHERRY )LU

MATTHEW ARIARATNAM

SUNKOSI (SUNA) GALAY-TAMANG

KIMBERLY SKYE RICHARDS

KELLY MCINNES

FUTURE INTERVIEW QUESTIONS FOR CASE STUDIES

FUTURE SURVEY QUESTIONS

QUOTES AND METAPHORS

THE ARTISTS OF THE ONLY ANIMAL’S ARTIST BRIGADE

APPENDIX 1: IRRESISTIBLE WORLDS INTERVIEW REPORT

APPENDIX 2: ARTIST BRIGADE TO THE REPORT

Artist Brigade Analysis:

1. Introduction

The Only Animal, a theatre company founded in 2005 by Kendra Fanconi and Eric Rhys Miller, creates immersive performances that arise from a deep engagement with place. In September 2021, The Only Animal brought together the Artist Brigade, initially a cohort of 100 artists that rose to meet the challenge of the climate crisis. In February 2023, the Artist Brigade is looking to expand this work nationally through our contributions to the collective research project, Irresistible Worlds.

The Artist Brigade grew out of conversations held between The Only Animal and the David Suzuki Foundation. In 2018, Kendra Fanconi, the Artistic Director of The Only Animal, had a series of meetings with the David Suzuki Foundation (DSF) about their interest in working with the arts in their climate communications. Sherry Yano and Jodi Stark were two key connections at DSF. Fanconi says:

I remember the moment when Sherry told me that when trying to mobilize people on climate, she considered the fact-based approach ‘dead’. She believed that we needed the artists. Jodi then brought up a few things where she wanted to invite artists in. On the fly, I came up with a few ideas that we got excited about. And in that conversation, we talked about the need for an Artist Brigade. Fanconi’s interaction with DSF helped spark the idea for the Artist Brigade.

Thereafter, in May 2019, Fanconi was asked to be the keynote speaker at a Climate Narratives Conference at Simon Fraser University. This conference aimed to bring together people in the climate movement who tell the climate story: journalists, faith leaders, Indigenous knowledge holders, policy people, climate science communicators, scientists, and environmental organizations, with the recognition that traditional fact-based communications don’t create change. Fanconi explains:

I was the only artist there. I thought there were probably other artists who wanted to collaborate on climate andso I reached out by social media to my friends. Then, I brought to the conference a Powerpoint slide with the names of 100 artists who I personally knew wanted to collaborate. For the rest of the day, the conference attendees chased me, in the washroom lineup, at the buffet, asking “Which artist can I have?” And I tried to say,‘hey, this is only an example, you should reach out to the artists you know” and they said, “we don’t know any artists”, and I replied, “well, even the artists you follow on Instagram, there is so much willingness!”, and they said, “we don’t follow artists on Instagram”. Based on these conversations at the conference, Fanconi came to understand how siloed the disciplines are, and Fanconi believed that The Only Animal could try to create connections across disciplines.

The Only Animal has worked on the issue of forest conservation on the Sunshine Coast for several years. When an old-growth yellow cedar forest, Dakota Bear Sanctuary was threatened with logging, local advocacy partners reached out to ask whether The Only Animal could do something to help save the forest. The Only Animal invited 20 artists from a range of disciplines and lived climate experience to come up to the forest, and hear different perspectives on it, then develop and pitch ideas. The Only Animal then commissioned and produced 11 pieces for which Fanconi served as a dramaturg. The pieces addressed climate change and sought to help save the forest from being logged while also supporting the efforts of forest advocacy groups and the Skwxwú7mesh Nation in their action to defend the forest. This combination of activities became the prototype for the Artist Brigade fieldtrips. Through this process, Fanconi noted that many of the artists turned away from working within their usual artistic disciplines, and instead offered to make documentaries because they believed that sharing information about the forest within a documentary form would have a greater impact on audiences. Fanconi says, “Based on what we knew, we felt that sharing facts about the forest would not transform audiences’ behaviours towards the forest, and so we wondered how to encourage artists to make different kinds of climate art in the future.”

The Artist Brigade was formed to support artists in making work that provides inventive and revolutionary responses to the climate crisis. To that end, The Only Animal led the original cohort through a year-long dramaturgical process, including workshops and weekly engagement, that helped artists reconsider their work in relation to climate change. A key premise of their effort is that climate art is more effective when it moves away from instructing publics, and instead engages aesthetic form (e.g. colour, rhythm, harmony, etc.).

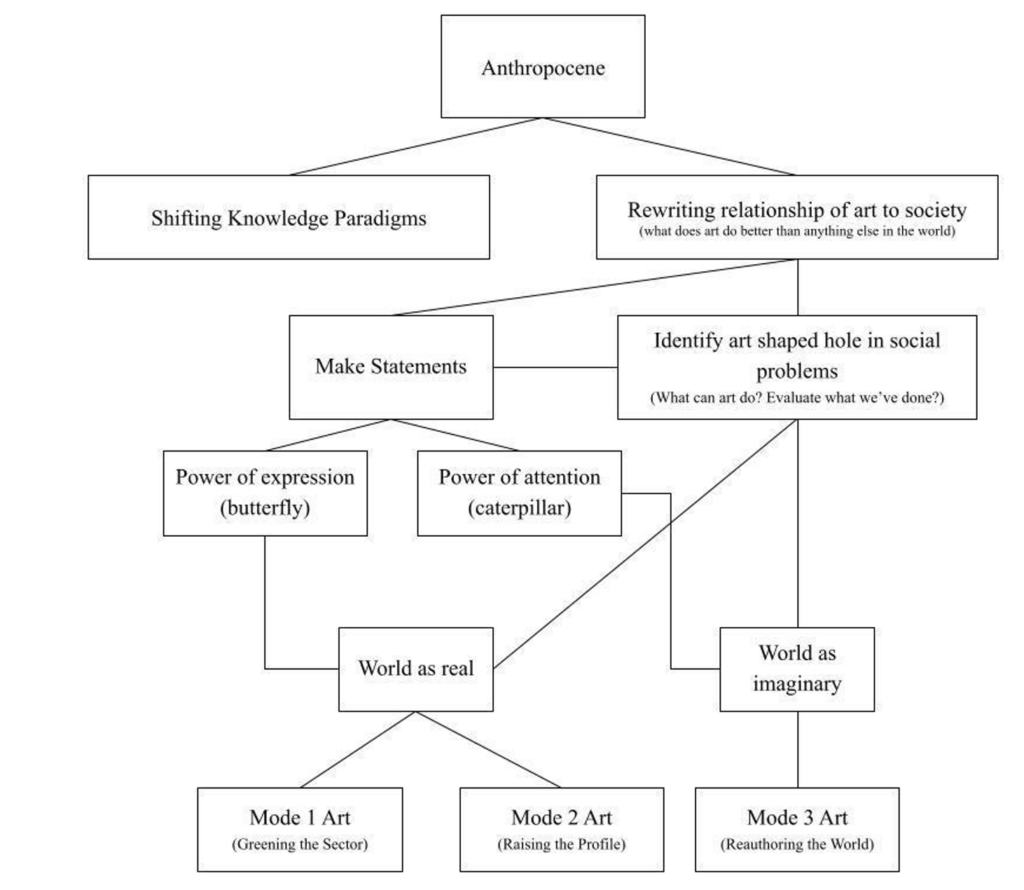

The Artist Brigade’s approach to working with artists can be further understood through David Magg’s three modes of making climate art, outlined in Art and Climate Change: Three Modes of Interaction. Mode 1, or “Greeningthe Sector,” focuses on reducing the environmental impact of making art. Mode 2, “Raising the Profile,” seeks to raise public awareness of the climate crisis, and often targets making change on a behavioural level. Mode 3, “Reauthoring the world,” “emboldens communities to find their own climate visions through the aesthetic” (Maggs, 61). Mode 3 involves using the arts to imagine and lure publics towards attractive, sustainable futures. Importantly, it transforms its audience, significantly, at the level of core values, identity, belonging, and worldview. Simply put, the Artist Brigade’s starting goal was to encourage artists to make Mode 3 art towards transformation at the level of identity, core values, worldview, and belonging.

This report considers how successful the Artist Brigade was in supporting the creation of transformational, Mode 3 artwork throughout their entire process including: 1) Recruitment; 2) Greenhouse workshop; 3) Field Trips and Pitches; 5) Commissioned Art; and 6) Activities and Pitches: 2022-23. In addition, we consider artists’ survey data and archival videos of Artist Brigade events to consider whether the artists pitched Mode 3 artworks. Following our analysis, we present the artists’ survey data, followed by seven Word Trees that demonstrate the interconnected, key concepts raised during the Greenhouse workshops. These words can also serve as keywords to code future qualitative data. Moreover, the report includes short profiles of 5 artists who went through the Artist Brigade process. These profiles are based on data that is currently available and could be expanded by conducting interviews with those artists in the future. Therefore, we also include a list of questions that could be used in future interviews or surveys. A final document includes quotes and metaphors raised by Artist Brigade members, that convey key ideas that emerged through the year long process. This report also includes an Appendix that documents a Zoom interview conducted by Alana Gerecke on 2 May 2023 for the Irresistible Worlds initiative. The interview engages Kendra Fanconi, Andre Forsythe from Canadian Climate Challenge (https://climatechallenge.ca/) and Irresistible Worlds, and ChantalBilodeau a leader in climate art and one of the originators of Climate Change Theatre Action (http://www.climatechangetheatreaction.com/) in a conversation about the unique role of the arts to mobilize climate action.

It is worth noting that the ideas and conversations documented in this report constitute a snapshot of the evolving and complex process that continues this effort to find language and Maggs, David. “Art and Climate Change: three Modes of Interaction”, Accessed March 2023. method to support climate art makers. This effort is at once iterative, sustained, and itinerant, and it takes shape around the practices and insights of a growing team of practitioners and thinkers.

As such, this report does not seek to sediment terminology or method so much as to share a time- stamped glimpse into the process to date.

2. Recruitment

The Only Animal strived to recruit a broad range of participants to the Artist Brigade, and the company reached out to artists via online platforms, professional networks, and personalized invitations to new collaborators. A first call to join the Artist Brigade was sent out on August 1, 2019, via The Only Animal’s online newsletter. Over the following months, additional announcements were made via Facebook, the BC Alliance for Arts and Culture, and the GreaterVancouver Professional Theatre Alliance websites.

Applicants for the first Artist Brigade initiative, Greenhouse, were prioritized for already being involved in climate activism or art, and for having diverse lived climate experience. Some applicants conveyed gaining diverse climate experience by living in remote regions of Canada or internationally. Other applicants reflected diversity related to their personal identities including their gender, race, disability, neurodiversity or Indigenous status. The Only Animal staff sought out and invited artists with whom they had not previously collaborated, especially IBPOC artists. Their effort to recruit diverse artists was wide-reaching, thoughtful, and exhaustive.

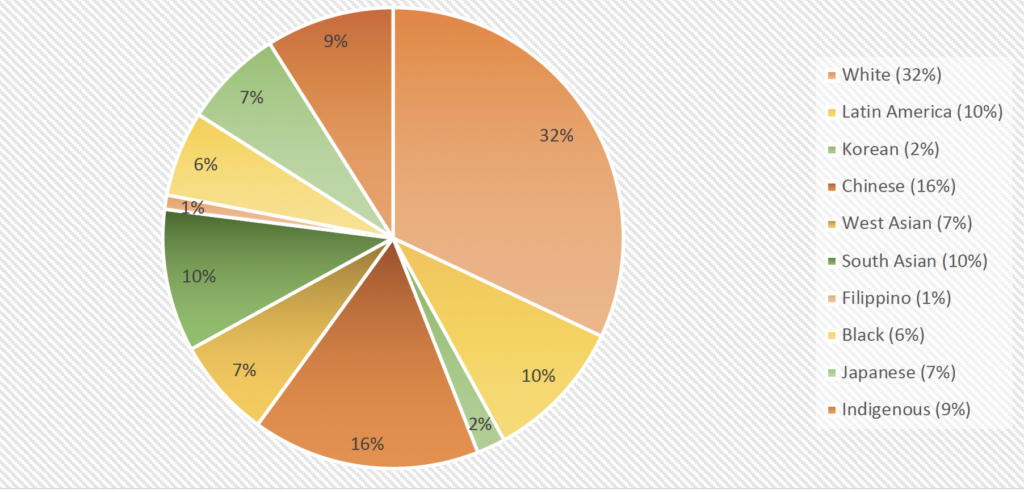

There were 228 applicants to Greenhouse, and the applicants submitted online forms that included information about themselves, their practice, and their relationship to climate change. Most Artist Brigade applicants were White (59%), emerging (53%), interdisciplinary (84%) artists (see Graph 1, 2, 4). The applicants reflected some of the ethnic diversity of British Columbia, as seen by comparing the Artists Brigade data to the 2021 Statistics Canada Census demographics. While the percentage of applicants that were White (59%) is less than the percentage of White people in the general population (65.6%), the percentage of applicants that were Indigenous (0.5%), Chinese (6%), or Black (0.5%) were less than the same within the general population: Indigenous (7.7%), Chinese (11%),Black (1.3%) (see Graph 4).

Importantly, these numbers need to be further contextualized given that The Only Animal enabled applicants to select “Mixed” (14%), which is a category that is not offered by Statistics Canada. Amongst the 33 applicants who self identified as Mixed, 6 people identified as part Indigenous, 11 people identified as part Chinese, and 4 people identified as part Black. From this perspective, the applicants to Artist Brigade were more diverse than the percentages above suggest (see Graph 5).

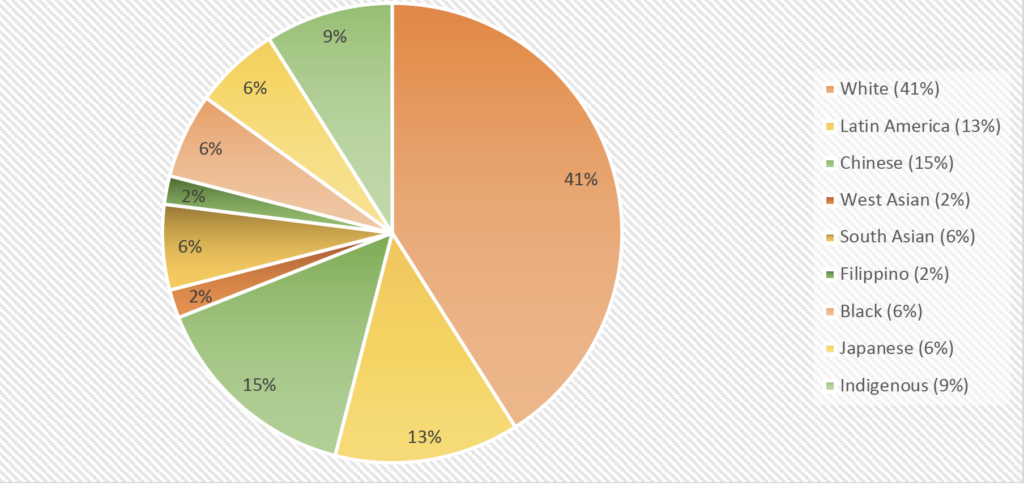

The ethnic makeup of the applicants can also be contrasted to the makeup of those selected to participate in the Artist Brigade. Artist Brigade participants also mostly White (44%), emerging (51%), interdisciplinary (89%) artists (see Graph 1b, 2b, 4b). Artist Brigade participants were more ethnically diverse than the applicants, including White (44%), Mixed (23%) and Chinese (10%). Amongst the 22 participants who identified as Mixed, 4 participants identified as part Indigenous, 7 participants identified as part Chinese, and 3 identified as part Black (see Graph 5b.

As part of the recruitment process, applicants were asked: “We are looking to represent a diversity of climate stories. What is your relationship to the climate issue?” The applicants responded to this open-ended question in different ways; while some applicants foregrounded their artistic process, others chose to focus on their personal lives and political choices. Through the applicants’ stories, it is possible to glean information about the applicants’ perspectives and goals and some of that information has been captured as percentages (see Graphs 6-13 in theRecruitment and Applications Summary). However, it is important to note that those numbers are biased because the applicants have all taken a different approach to answering the open- ended question. For example, while some applicants chose to talk about their gender identity within their allotted 200-word count response, others may not have raised their gender identity within their response, but this doesn’t mean that the applicant deems the topic to be inconsequential. Instead, Graphs 6-13 and Graphs 6b-13b should be read as a reflection of the themes that were commonly raised by multiple people, and the approximate percentage of applicants for whom those themes were most important. This type of thematic analysis is appropriate to studying the open-ended questions used in the Artist Brigade surveys and thematic analysis is used again in different sections of this report.

Beyond the applicants’ ethnic diversity, different climate experiences were exhibited by applicants who had lived abroad or in remote regions of BC or Canada. Although 86% of applicants live in the Lower Mainland of BC (Graph 7), 32% mentioned that they had experienced regional or international variations on climate realities (Graph 8). Similarly, amongst those recruited to join the Artist Brigade, 89% lived in the Lower Mainland of BC (Graph 7b), 36% mentioned that they had experienced regional or international variations on climate realities (Graph 8b). In addition, within their open-ended response, some applicants chose to convey their interest in exploring diverse perspectives on climate and art with the Artist Brigade; 12% conveyed their interest in IBPOC climate and art (Graph9) and 15% in Indigenous perspectives (Graph 10). Amongst those who joined the Artist Brigade, 16% conveyed their interest in IBPOC climate and art (Graph 9b) and 23% in Indigenous perspectives (Graph 10b).

In addition to having diverse lived-experiences of climate, applicants were also prioritized for already being involved in the climate crisis, and 99% of the applicants mentioned they had already acted against climate change at some point in their lives (Graph 11), and 100% of the participants had already taken action. Since many of the applicants did not specifically talk about their artistic practice within their application, it is not possible to accurately convey how committed artists were to making climate art before joining the Artist Brigade; however, this has beenincluded as a question to ask in future surveys (see Future Survey Questions).

Analysis of the survey data conveys common reasons why artists applied to the Artist Brigade including: wanting to make art that helps public’s connect with nature (31%), building community (22%), addressing climate anxiety (15%), accessing mentorship (6%), learning to work with youth (<2%), and learning how to connect with politicians (<2%) (Graph 12). Again, these percentages are approximate, but it is important to note that about 15% of the applicants were experiencing intense climate anxiety that caused them to slow their artistic practice, and they applied to the Artist Brigade to work through that anxiety.A question regarding climate anxiety was posed again following the first Artist Brigade meeting, and so it is possible to interpret whether this objective was met and will be discussed in the next section of this report.

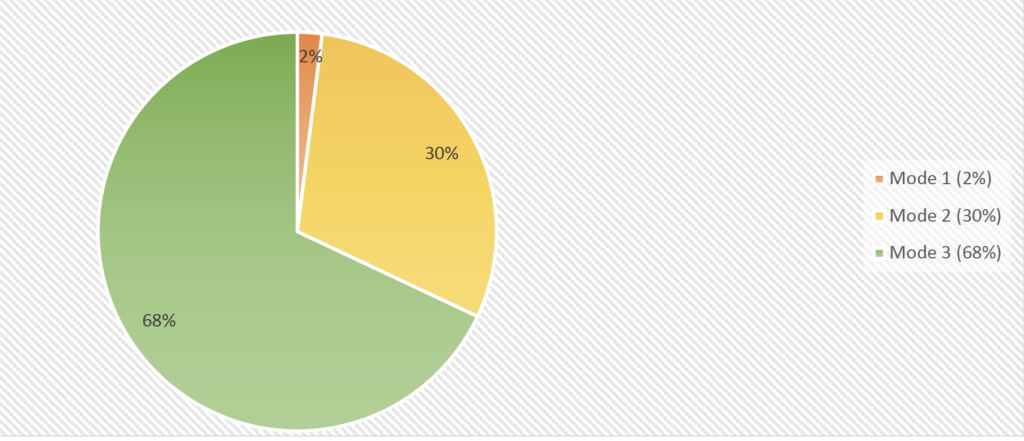

Lastly, the artists’ open-ended responses provide some insight into how artists perceive of their work in relation to climate change, and their responses can be categorized using Magg’s Mode 1 (18%), Mode 2 (43%) or Mode 3 (15%) (Graph 13). The percentages were similar amongst the participants, Mode 1 (17%), Mode 2 (43%) and Mode 3 (13%) (Graph 13b). While these percentages are approximate, the numbers suggest that artists had more to learn about making impactful Mode 3 art by joining the Artist Brigade.

3. Greenhouse

Applicants recruited to the Artist Brigade were invited to attend Greenhouse, a two day, paid intensive focused on climate literacy and the role of the artists in the climate emergency. Video recordings were made of the events that took place, a follow up survey was completed by the participants, and this information is summarized in this section of the report, and in Graphs 14-20 below. Greenhouse, hosted at the University of British Columbia Botanical Garden in September 2021, opened with a commissioned piece created by sχʷəy̓ em̓ theatre artist Quelemia Sparrow. Sparrow’s creation was a 30-minute, interactive presentation that welcomed participants through a form of place-based ceremony. Following this Land Acknowledgement, the context for where the work was happening, The Only Animal welcomed the group by presenting a Climate Acknowledgement which brought context to the when, as far as defining this climate moment.

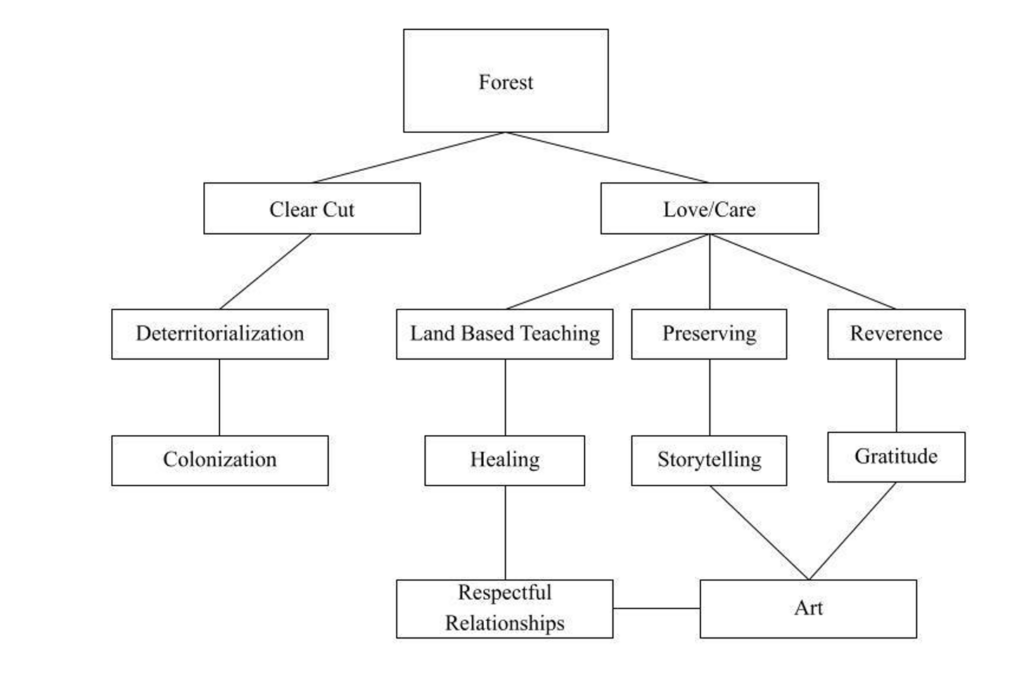

This was done by 12 year-old Larkin Fanconi Miller, who described their own climate futures by meeting members of the Artist Brigade who were in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s. The Only Animal then provided a clear description of how the days would unfold, emphasizing ways the participants could prioritize their well-being throughout the two-day intensive. The Brigade was then divided into smaller groups, where they cycled through a series of 7 workshops led by artists, academics and environmental experts and educators. Each workshop made use of different methodologies and led participants to discuss a range of topics. The methodologies are outlined here below, and key themes raised in the workshops are summarized in Word Trees 1-7.

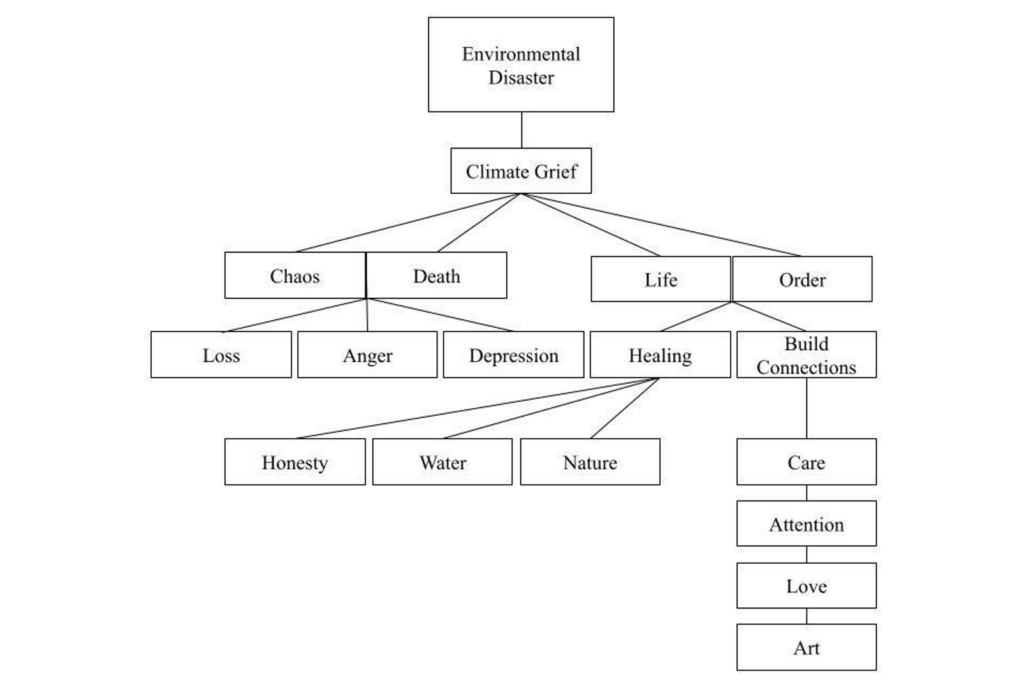

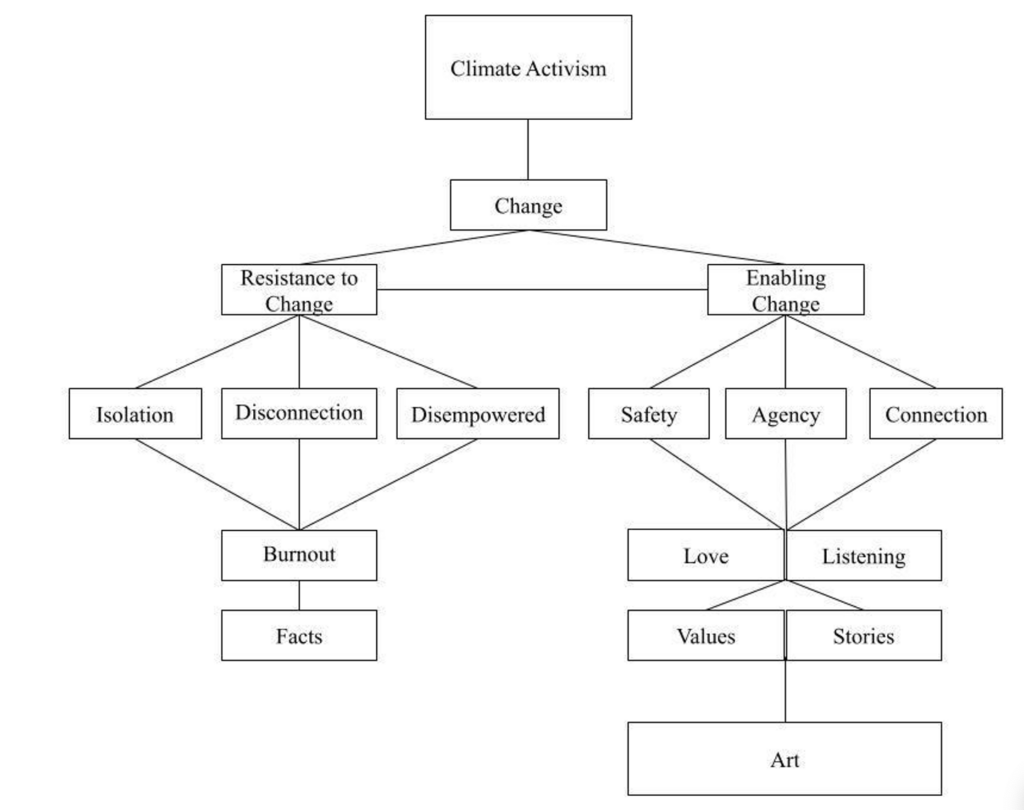

A workshop led by Corey Matthews, a death doula and artist, was entitled “Climate Grief.” Matthews contends that our contemporary society has not enabled people to grieve the loss of nature and destruction of life that surrounds us. She hopes the workshop will be a safe place for people to begin grieving and to consider the role that art might play in the grieving process. Matthews reads a poem, compassionately reviews COVID protocols, tells stories, asks questions, and invites participants to share how the climate crisis scares them. Matthews suggests love can bring people out of grief, and art is a form of love that allows us to give attention to other people and the world. The key themes raised within this workshop are outlined in Word Tree 1.

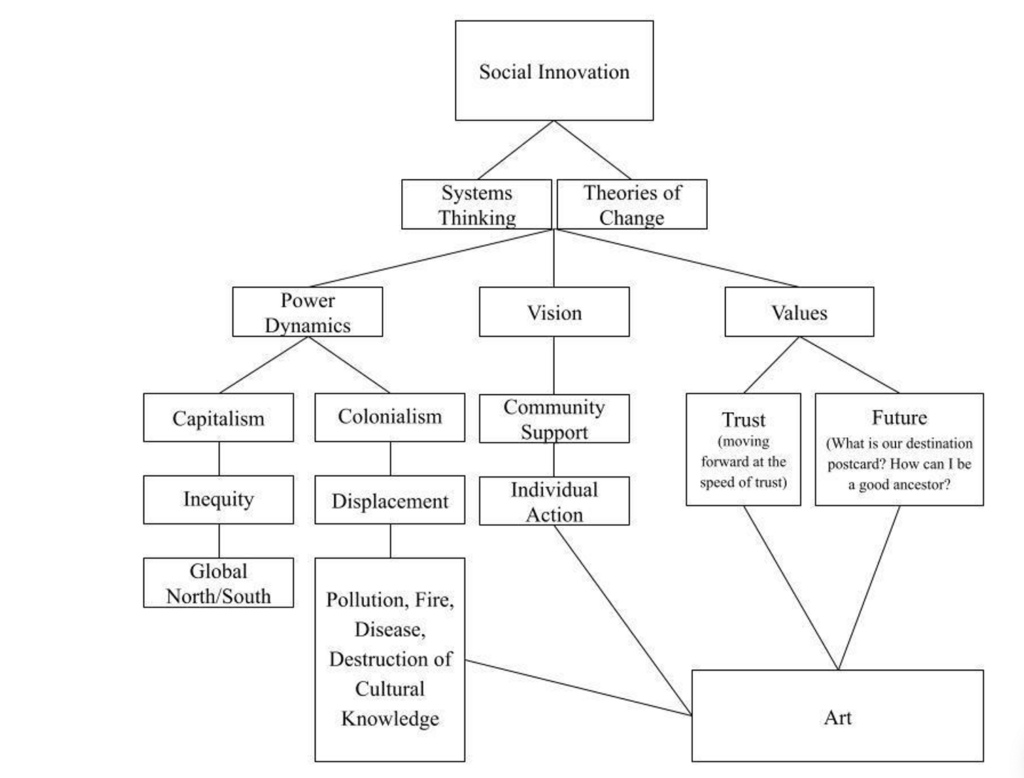

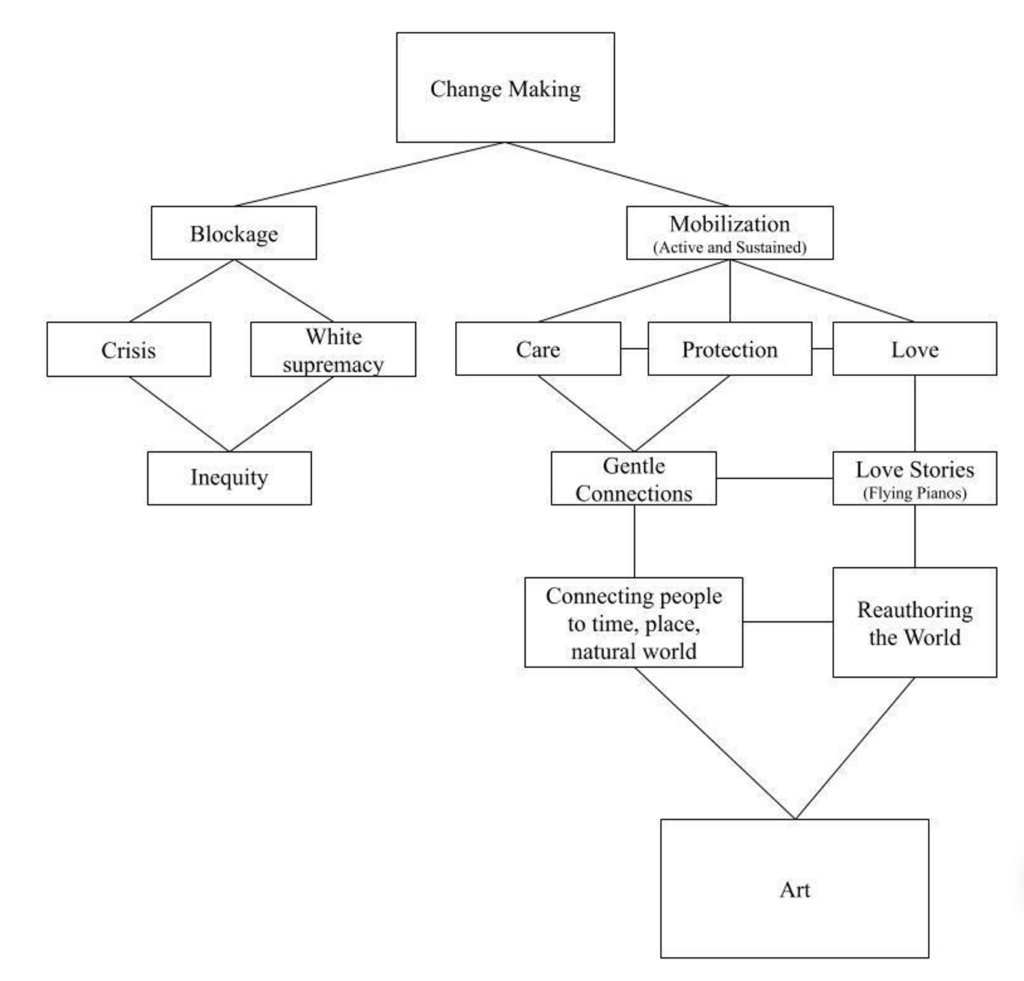

A second workshop was co-hosted by environmental experts and educators Oliver Lane and Tara Moreau. The second workshop was divided into two parts entitled: “All Hands On Deck: Climate Crisis” and “Solutions-based System, UNLEASH.” Lane and Moreau begin the workshop by reviewing core concepts such as the definition of climate change, collective change, and adaptation. Next, the facilitators introduce UNLEASH, a social innovation methodology that helps people identify the root causes of social issues and envisions solutions to address those fundamental causes. Lane and Moreau suggest artists can create more impactful work if they address the root causes of environmental issues. Within the workshop, the artists are invited to practice identifying root causes by making problem framing trees. Working in small groups, the artists created a short artwork that depicts solutions to the root causes they had previously identified. The artists then presented their alternate visions of the future to one another, and their solutions were documented by an “Idea Catcher.” Land and Moreau’s workshops lead to a rich discussion of climate change, and the key topics discussed are captured in Word Tree 2.

A third workshop, “ENGO Problems for Artists,” was hosted by Sherry Yano, engineer, environmentalist, and non-profit manager. Yano argues that technology and science have not brought publics to change their behaviours, and she suggests that artists might bring about change by telling stories and making new meanings. Yano invites the participants to share how they felt during “aha! moments” or moments of transformative change. She also asks the participants to identify what they love doing, who is their audience, and what futures they hope to cultivate. Participants are also encouraged to share their stories, and to build their own diverse and creative initiatives. Key themes raised in Yano’s workshop are summarized in Word Tree 3.

A fourth workshop, “Role of the Artist in the World After This,” was led by artist and public scholar, David Maggs. During the workshop, Magg’s presents his theory of the 3 modes of climate art interaction. Maggs describes both the context in which the modes were developed, as well as their definitions. Participants are given the opportunity to ask questions about the modes, and key themes from the lecture are summarized in Word Tree 4.

A fifth workshop, “Artists at Work in the Climate Movement” was hosted by The Only Animal co-founder and Artistic Director, Kendra Fanconi. Fanconi asks: “how do we create change with art?” Fanconi proposes artists can meet people in their emotional world to create collective transformation. To demonstrate this perspective, Fanconi asks participants how their bodies feel when they hear the scary facts of climate change: frozen, contracted, blocked. Fanconi suggests mobilization and movement need melted hearts instead of frozen, immobile ones. She further describes how art can help melt hearts by conveying hope and beauty. Fanconi shares her own journey through this process and invites participants to think through practical art-making scenarios as a group. She recommends artists reach out to organizations to make art with them. Fanconi respectfully responds to participants’ comments and skillfully ties comments back to the main group discussion. Key themes raised in this workshop are summarized in Word Tree 5.

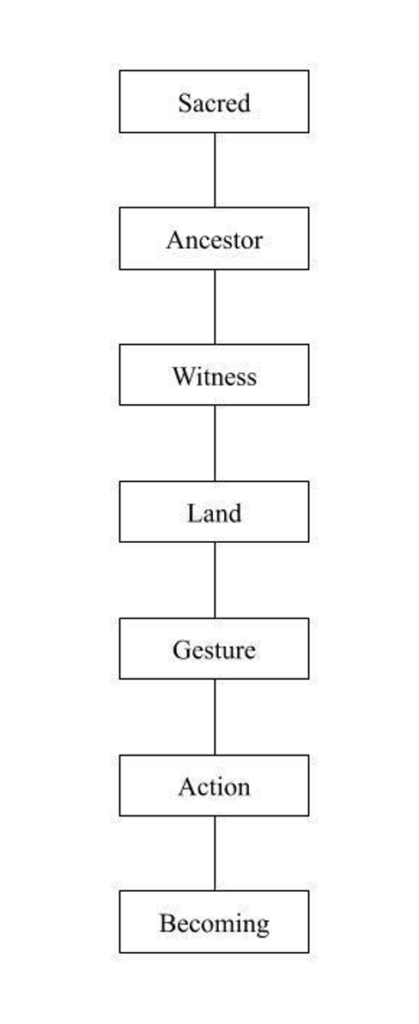

A sixth workshop, Body as Landscape: Indigenous Lens on Climate,” was led by Ojibwe/Swampy Cree and English/Irish descent Indigenous theatre artist Lisa Cooke Ravensbergen. The author of this report is not Indigenous, and so the report does not attempt to convey the significance of Ravensbergen’s workshop, nor extensively share Ravensbergen’s knowledge and process. Instead, the report briefly describes what took place during the session. Ravensbergen invites participants to ask a stone to join them in the session. The stone represents an ancestor who witnesses the participant’s sacred gifts. The stone is left on the land at UBC, creating a relationship between theparticipant, the land, the sacred, and the ancestor. Ravensbergen’s process transforms the participant’s relationship to the land. A summary of the key themes raised in this session is presented in Word Tree 6.

Finally, a seventh workshop, “Artists Journey in Environmental-Activism Through Indigenous Lens,” was led by Coast Salish, Welsh, and European Jewish Indigenous dance artist Tasha Faye Evans. As with Ravensbergen’s work, the significance and breadth of Faye Evans’ work is not presented in this report, and, instead, the session is briefly described. During her session, Faye Evans tells a story about her relationship to a forest, and how she uses art in service of protecting territories and reclaiming her Indigenous identity. Faye Evans calls upon participants to identify their values, and to recognize how art can create ripples that cause wider change. A summary of the themes foregrounded in this session is outlined in Word Tree 7.

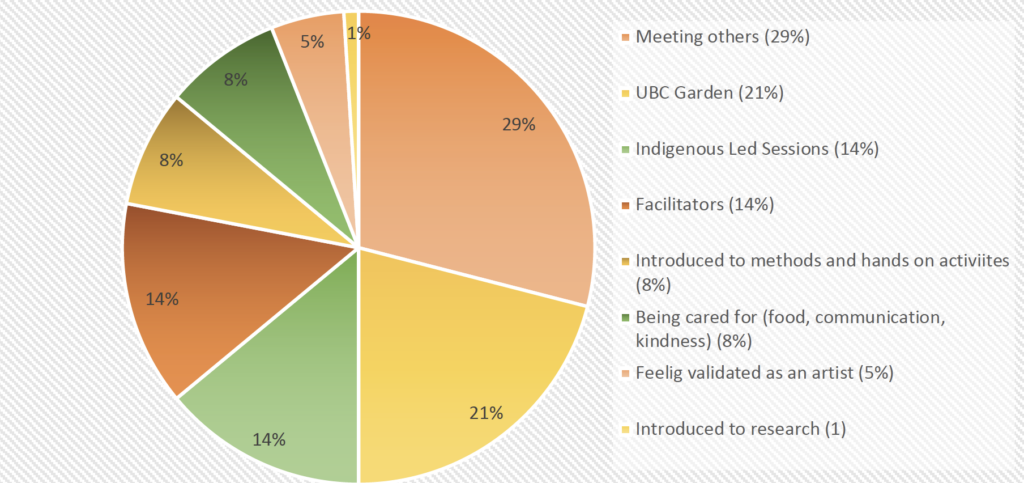

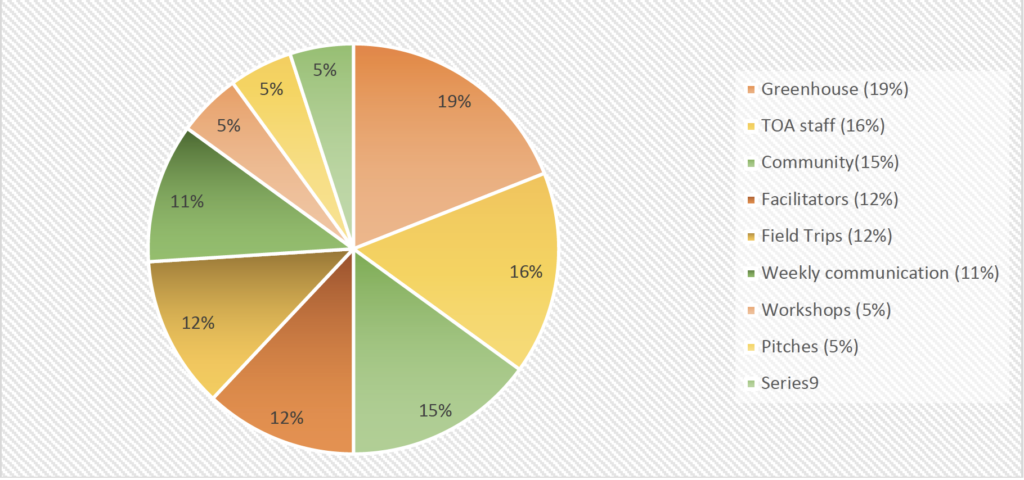

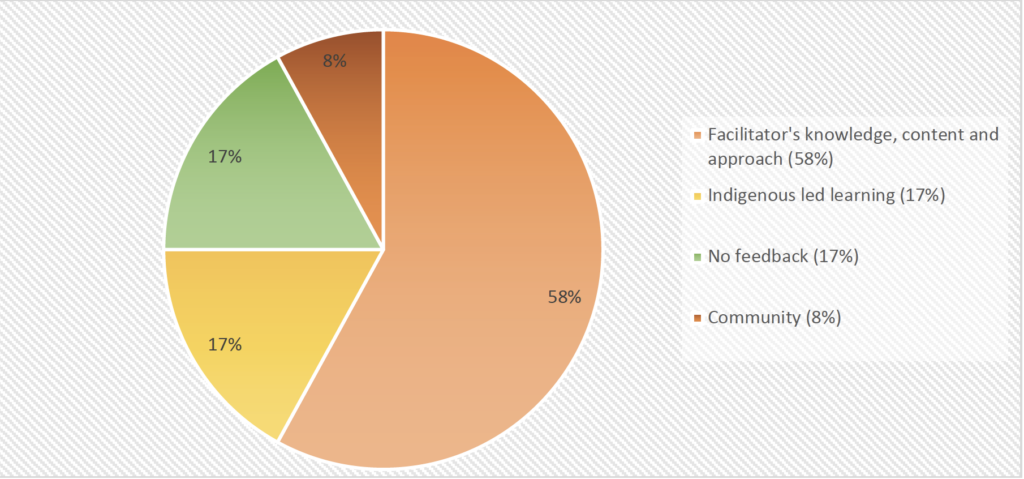

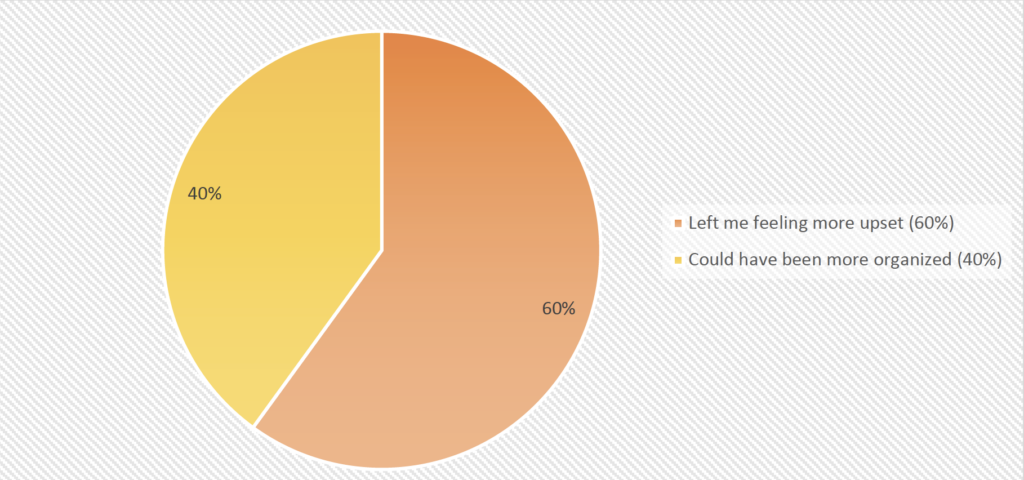

In addition to the video documentation of the Greenhouse sessions, The Only Animal collected feedback from 56 participants via a survey. Some of the open-ended survey questions addressed what the participants liked and disliked about Greenhouse. The top reasons that applicants liked Greenhouse were building community (29%), UBC botanical garden (21%), Indigenous led sessions (14%) and the facilitators (14%) (Graph 14). While these percentages are approximate, it is interesting to compare what the participants enjoyed about Greenhouse to the goals artists conveyed in their applications. For example, one of the reasons that the artists applied to the Artist Brigade was to learn from Indigenous artists, and the Indigenous led sessions were one of the most appreciated aspects of Greenhouse. In addition, although the applicants didn’t convey their interest in meeting for Greenhouse in a beautiful space, the site upon which Greenhouse took place was important to many of the participants. Moreover, 22% of applicants conveyed their interest in building community, and this aspect of Greenhouse was most appreciated by participants. This data suggests that some applicants achieved one of their goals for joining the Artist Brigade.

The survey also collected open-ended feedback about what participants disliked about Greenhouse. Notably, 29% of participants had no negative feedback about Greenhouse. Some of the other feedback included: wanting more unstructured time (22%), hoping for more applied workshops (15%), and accessibility (7%) (Graph 15). These concerns might be addressed in future Artist Brigade workshops.

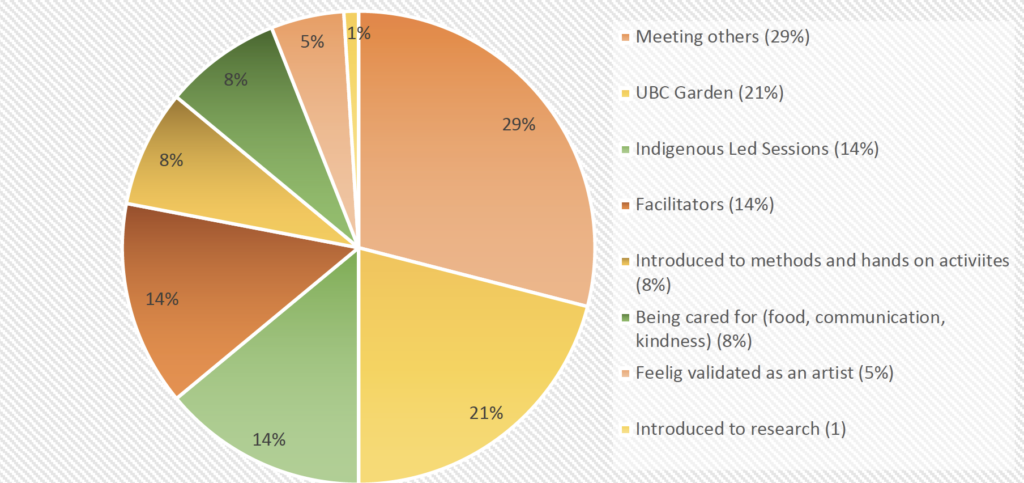

The survey also sought out feedback about whether the participants’ level of climate anxiety decreased (44%), increased (13%) or stayed the same (43%) by participating in Greenhouse (Graph 16). In addition, the survey asked participants how Greenhouse impacted their climate anxiety, and responses included: learning that art matters in climate action (42%), finding community (28%), addressing grief (6%), and learning facts (5%) (Graph 17). The 42% of artists who noted that learning that art matters in climate action suggests that Greenhouse successfully empowered and motivated artists to continue working in their field. As previously mentioned, 15% of artists applied to Artist Brigade to work through their climate anxiety, indicating that directly addressing climate anxiety within one of the Greenhouse workshops was a valuable goal.

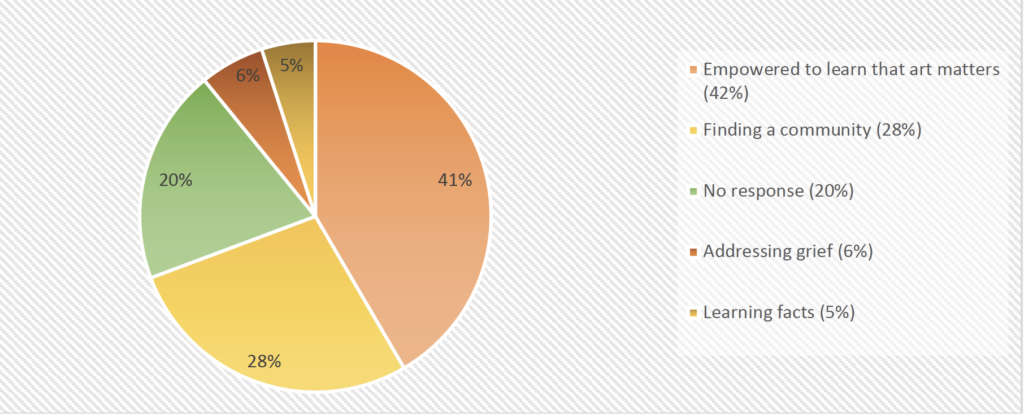

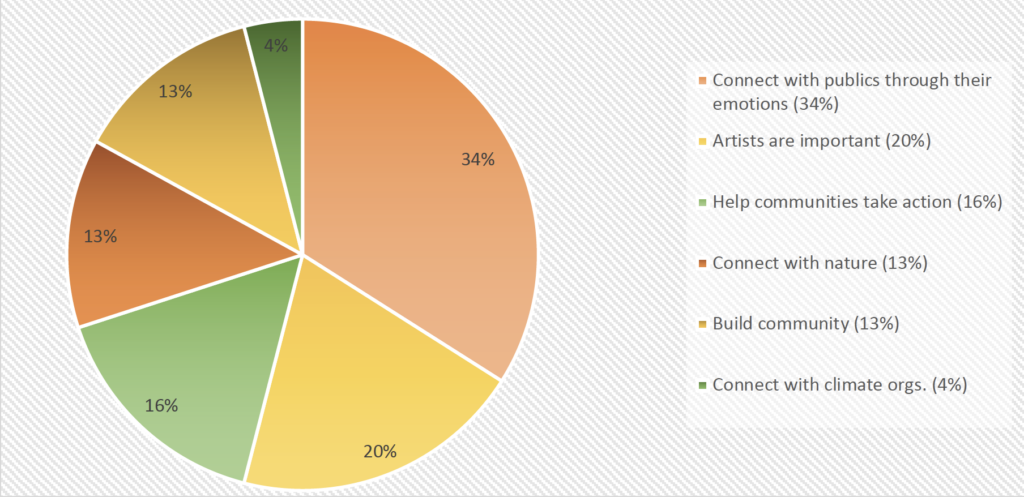

Moreover, the survey questioned artists about their understanding of their role as an artist in climate action after having participated in Greenhouse workshops. The roles outlined by artists can be classified by Magg’s Modes: Mode 1 (2%), Mode 2 (30%), and Mode 3 (68%) (Graph 18). By contrast to the artists’ applications to Greenhouse in which only 15% of the artists focused on Mode 3, it can be interpreted that Greenhouse led more artists towards making Mode 3 art (percentages are approximate). Finally, 77% of the artists indicated their intention to make climate-engaged art immediately following Greenhouse (Graph 20). It is likely some of this new art would aim to be Mode 3.

4. Field Trips and Field Trip Pitches

Following Greenhouse, artists were invited to take part in a field trip organized by The Only Animal. The key goal of the field trips was to give participants an embodied experience of climate problems and climate solutions and to inspire them to create artwork on climate. There were four field trips the artists could select from, though capacity was limited so not every participant was able to take part in their first choice. The Only Animal produced short video clipsthat outlined some of the aspects of the field trips, and following the trips, artists were asked to pitch ideas for climate artwork that The Only Animal could commission in the future.

Participants also completed a survey following the Artist Brigade’s first year of work about the field trips. Information gathered from the video clips, artists’ pitches, and surveys is summarized in this section of the report, and in Graphs 21-25 and Graphs 31-34 below.

The first field trip took place on January 26th, 2022, on the Sunshine Coast, and was entitled “Forest in Danger.” For this trip, 25 participants were invited to the Songbird Forest, which is slated for logging. The group was welcomed by hereditary chief of the shíshálh Nation, hiwus, Calvin Craigon, who described the significance of the forest to his nation and encouraged the group to pay close attention to their senses as they walked through the forest. Bob O’Neil and Ross Muirhead from Elphinstone Logging Focus, and Sarah Lowis-Holliday from Living ForestInstitute, also shared their perspectives on the forest. In addition to being immersed in the forest, the participants also took part in group discussions.

The second field trip took place at Trillium Park in Vancouver, on February 26th 2022, and was entitled “Co-Creating a culture of Stewardship: Cloth, Plants and Place.” 17 participants attended this hands-on field trip, where IBPOC facilitators presented on different cultural and national contexts related to textiles, climate, and heritage. Sḵwx̱wú7mesh artist, Meghan Innes, welcomed the participants to the land and led one of the sessions on fibre and identity. In addition, CZarina Lobo led a session on her textile work with indigo which is connected to her Indian heritage. Sharon Kallis, from EartHand Gleaners, offered a workshop on making rope from stinging nettle, which is from herCeltic heritage.

The third field trip, “The Artist’s Part,” took place at the Van Dusen Botanical Gardens in Vancouver on March 23rd, 2022. This trip was planned to take place in Vancouver to accommodate participants who could not travel far from the city due to their accessibility needs, work schedules, or other responsibilities. For this trip, 13 participants were invited to consider their art in relation to other professionals who help tell the climate story such as journalists, activists, government officials, and sustainability experts. Participants met representatives from the City of Vancouver Resilience Office, Climate Disaster Project, and the Georgia Strait Alliance, and spoke about topics including the heat dome, friendship, behaviour, and advocacy. The session included a presentation by Lucero Gonzales who focused on her work with orca whales. In addition, one of our facilitators, Lolehawk (Dr Laura Buker) from the Sto:lo nation, had intended to present on salmon in the Fraser River but withdrew after contracting COVID-19.

“Sustainable Living,” the fourth field trip, took place on Gambier Island on April 21,st 2022.

The 22 participants travelled to Gambier Island together, and visited Colin Cooper, a core member of The Only Animal, at an off-grid homestead. Cooper showed participants the food, water, and energy systems on the 50-acre homestead, and the group discussed topics such as sustainability, moderation, responsibility, nature, and hope. Hereditary chief of the shíshálh Nation, hiwus, Calvin Craigon, as well as ecologist and educator, Tim Turner, spoke with the group about what transformation and sustainability meant to each of them.

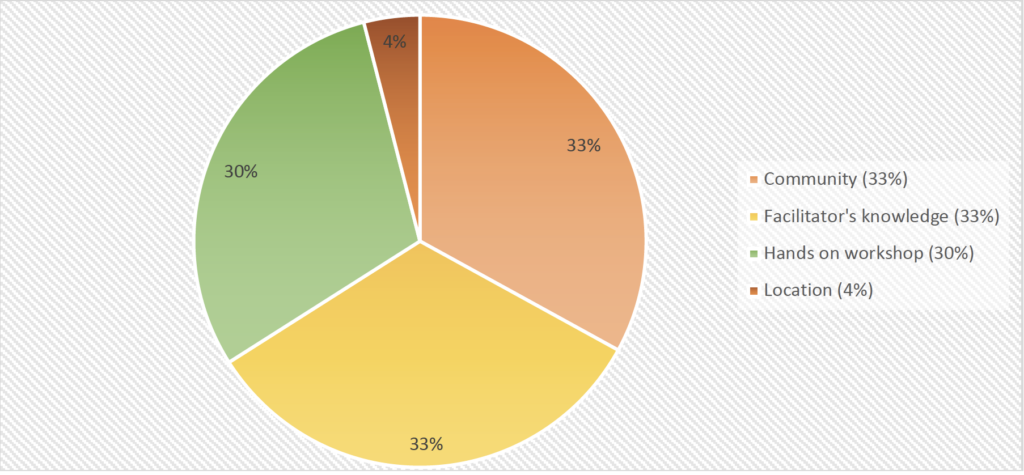

Survey feedback about the field trips was generally positive. 25 participants responded to the open-ended question about why they liked the field trips. Their top three answers were: building community (33%), facilitator’s knowledge (33%), and hands-on/immersive learning (30%) (Graph 30). The fact that 30% of participants conveyed their appreciation for being immersed in an embodied and hands-on experience suggests that the key goal for the field tripswas met.

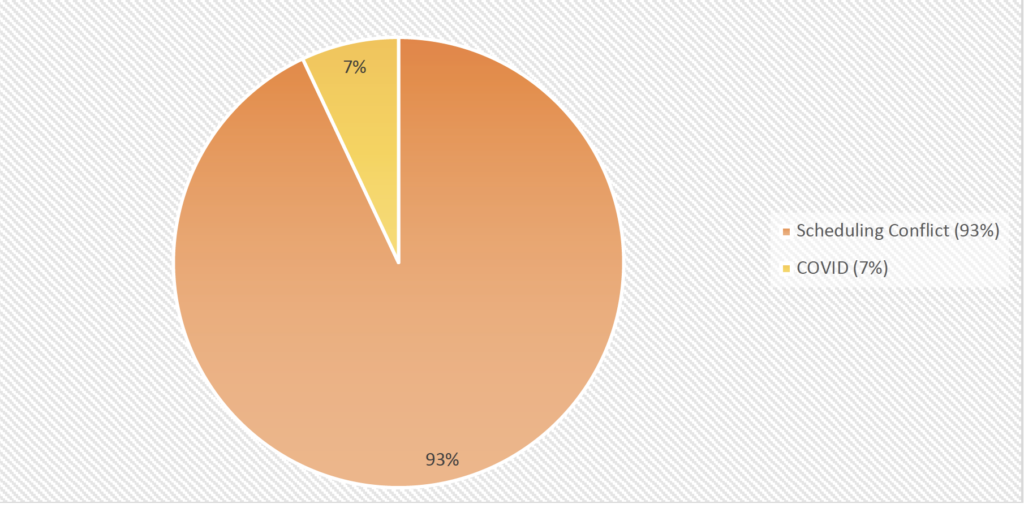

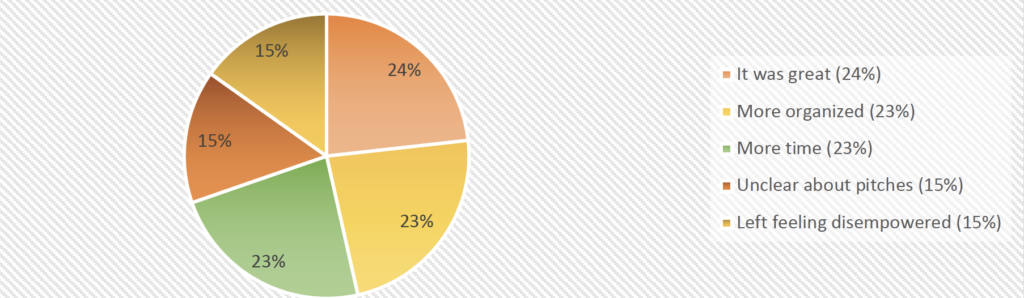

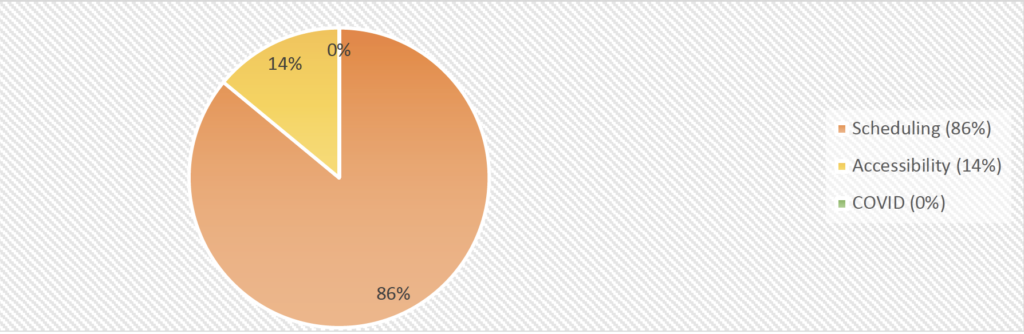

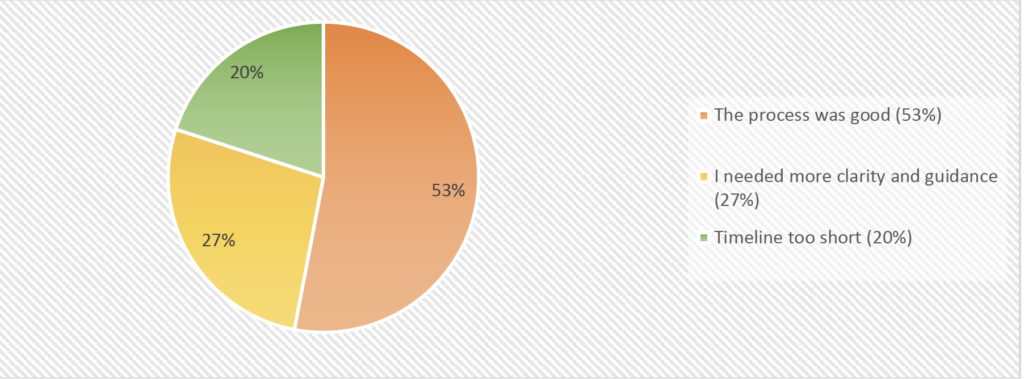

Moreover, when asked what participants disliked about the field trips 24% had no negative feedback to share, while 23% wished they had more time for the field trips. Others (15%) suggested they would have appreciated more clarity about the art pitch process (Graph 31), though it should be noted that in a later survey, 53% (see Graph 34) of respondents indicated the pitch process was clear and appropriate. Moreover, 15% of participants indicated the field trips led them feeling disempowered (Graph 31), which may have been counteracted if there had been the opportunityfor more sustained engagement as a group. In addition, as depicted in Graph 33, the top reasons participants did not take part in field trips were due to scheduling conflicts (86%), and accessibility (14%).

Following each field trip, participants were invited to pitch an artwork to be considered for a future commission by The Only Animal. It is notable that artists were paid $200 to present a pitch, given that this form of labour is rarely compensated within the art sector. The Only Animal provided a framework for developing pitches but did not support artists to develop pitches with one-on-one support. Approximately half the number of participants to each field trip presented a pitch. The types of pitches developed can be categorized using Magg’s modes. Following “Forest in Danger,” 12 pitches were made with 30% Mode 2, and 70% Mode 3 (Graph 22). “Co- Creating a culture of Stewardship: Cloth, Plants and Place” prompted 7 pitches, of which 40% were Mode 2, 15% were Mode 3, and another 40% would be Indigenous led practices (Graph 23). The 7 pitches following “The Artist’s Part,” included 60%Mode 2 and 40% Mode 3 (Graph 24). Finally, the 10 pitches for “Sustainable Living,” were 10% Mode 2 and 90% Mode 3 (Graph 25). Overall, this analysis suggests that of the 36 pitches in total, approximately 35% were Mode 2 and 65% were Mode 3. It should be noted the field trips that had more of an issue-based focus, such as helping Orca whales, tended to bring about more Mode 2 pitches.

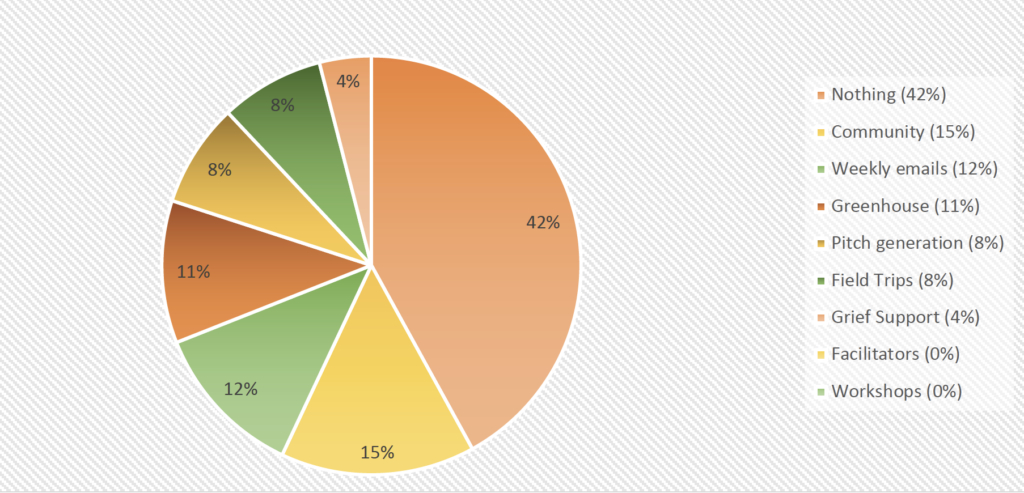

Following the completion of the field trips, The Only Animal issued a survey, consisting mainly of open-ended questions, to collect participants’ feedback on the Artist Brigade process for 2021-2022. There were 25 respondents to this survey, but the respondents did not always answer all the questions. Some of the key findings from this survey are that the Artist Brigade process changed 92% of the participants’ artistic processes (Graph 36), and this was mostly achieved by building community (41%), by learning new methods and approaches (27%), and conveying art is important to climate activism (14%) (Graph 37). Moreover, amongst the participants, 72% were highly appreciative of the weekly emails sent out by The Only Animal (Graph 35), since the emails helped build a sense of community and were informative. Finally, when openly asked for general feedback about the Artist Brigade, 77% simply thanked The Only Animal for their excellent work.Given that taking part in the Artist Brigade changed 92% of the participant’s artistic processes, it can be concluded that The Only Animal offered an embodied, transformative experience to participants, which modelled the aims of Mode 3 art making.

5. Commissioned Art

The Only Animal commissioned 4 of the 36 pitches by artists from 2021-2022. The four artworks were selected for being achievable within the given timeline and budget, and for developing a Mode 3 and/or Indigenous-led proposal. Documentation about the four artworks, including video recordings and text, are available on The Only Animal website (https://www.theonlyanimal.com/the-artist-brigade/).

The first commissioned artwork, In the SongBird Forest, is by Runaway Moon Theatre and directed by Cathy Stubington. This artwork was pitched following the “Forest in Danger” field trip. SongBird Forest is a site-specific performance that portrays six performers wearing large blue masks siting or laying quietly in a forest. These masked characters, called the Blue People, were originally developed for a previous project by Runaway Moon. The artists decided to reuse the Blue People for SongBird due their appealing quality of curiosity and openness, and their abilityto help alter the audience’s perception of the forest as being a habitat for beings.

Additionally, the Blue People are photogenic due to their colour, form and movement, and are appealing for an intergenerational audience. Overall, the Blue People helped audiences become more aware for the Songbird Forest and its plight. The work also produces compelling images to be used by activists in their efforts to protect the forest from logging. The Blue People were performed by Artist Brigade participants including Mohammed Zaqout, Matthew Ariaratnam, Chantal Gering, Leah Day and Nita Bowerman, and allowed Artist Brigade artists to share further techniques for making climate art. In 2023, it was announced that the Songbird Forest has been removed from the Sunshine Coast Community Forest’s logging schedule in response to public pressure.

The second commissioned project, Remembering Mothertongue Project, by Sunkosi Galay- Tamang was pitched following the “Co-Creating a Culture of Stewardship” field trip. The textile-based project explores the relationship of animals and the land, and the ecosystems that enabled ancestors to survive. The project introduced collaborating artists to the process of sheepskin tanning and corn husk weaving as a way of inspiring IBPOC artists to write poetry, and the creation of a Zine that includes the work of Eddy van Wyk, hoddie browns, Jamjna Galay-Tamang, KarmellaCen Benedito De Barros, Kwetasel’wet/Steaphanie Wood, Miki Wolf, Nico Rojas, Ogheneofegor Obuwoma, Pah’sung Pasang Galay, Sacha Ouellet, Susaan Yáñez- Kallfümalen.

Lastly, the fourth commissioned artwork, 來跟我在林里做夢 Come dream with me in the forest, by Wen Wen (Cherry) Lu, was pitched following “The Artist’s Part” field trip, and was inspired by conversations held at Greenhouse regarding Indigenous place names. The artist was interested in how place names convey Indigenous relationships to land, and they wished to explore how ancient Chinese calligraphy relates to nature. For example, Lu shows how words like ‘tree’, ‘forest community’ and ‘dream’ share the same root image, which conveys how Chinese culture has valued the environment. The artwork seeks to open conversations about the climate crisis with a wider demographic, particularly with people who may have lost their connection to land through immigration including the Chinese diaspora. The work was made with collaborating Artist Brigade artist, Celia Leung, and Robyn Jacob.

6. 2022-2023: Pitches and Activities

In October 2022, The Only Animal made a second call for pitches from the Artist Brigade. This process is a 7-month program in which the artist received mentorship to develop a work, as well as support with disseminating the piece. Artists were compensated $200 for their pitches, and selected artists were awarded a budget of $10,000 to develop their work. The mentorship took the form of bi-weekly group check-ins, bi-weekly individual mentorship, support with producing, grant writing, dissemination and networking with organizations and experts. Of the 34 pitches, 6% are Mode 1, 26% are Mode 2, 62% are Mode 3, and 6% are Indigenous-led (see Graph 39).

In 2023, The Only Animal will also invite 15 Artist Brigade members for a 2-day “maker lab” with scholars working in the climate crisis. Part of the lab will take place over Zoom, and a second part will take place in-person at the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies at University of British Columbia.

Artist Brigade Surveys Analysis

1. Recruitment: Applications Summary (228 Applicant responses)

Graph 1: Career Stage

| Emerging | Mid-career | Established | |

| % | 53% | 36% | 11% |

Graph 2: Discipline

| Interdisciplinary | Fine Arts | Theatre | Film | Music | Design | Dance | |

| % | 84% | 7% | 5% | 1.25% | 1.25% | 1% | 0.5% |

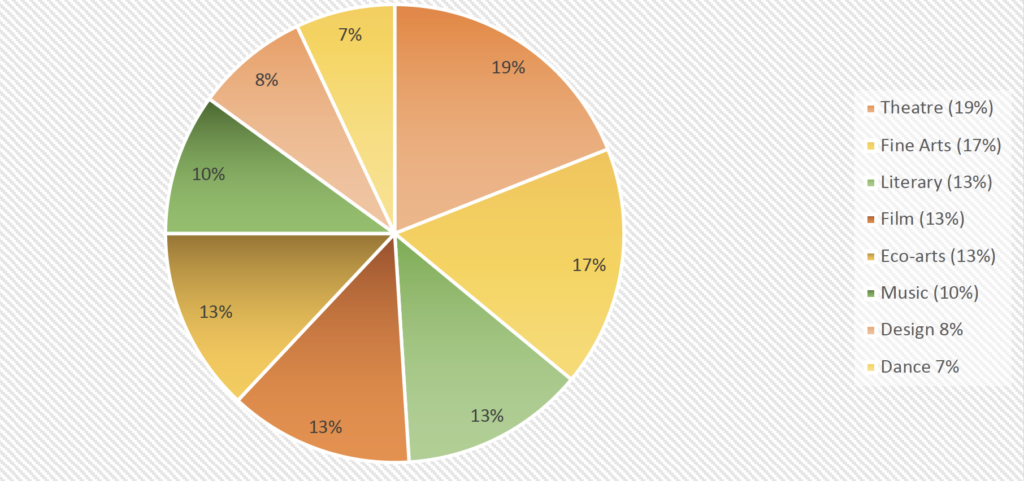

Graph 3: Distribution of Interdisciplinary Artists (192 artists)

Graph 4: Ethnicity

| White | Mixed | Chinese | S.Asian | W.Asian | LatinAmerican | Filipino | Korean | Indigenous | Black | Prefer not tosay | |

| ArtistBrigade % | 59% | 14% | 6% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 6% |

| GeneralPopulationBC % | 65.6% | NA | 11.2% | 9.6% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 3.5% | 1.5% | 7.7% | 1.3% | NA |

Graph 5: Mixed Ethnicity Breakdown for Applicants

Graph 6: Indigenous Self-Identified

| Non-indigenous | Indigenous | |

| % | 98% | 2% |

Graph 7: Geography

| Lower Mainland | Vancouver Island+ Coast | Kootenay | Thompson-Okanagan | Other | |

| % | 86% | 10.5% | 2% | 1% | 0.5% |

Graph 8: Applicants with international or regional lived experience of climate change

| Yes, I have diversity of livedexperience with climate change | No comment |

| 32% | 68% |

Graph 9: Applicants expressed specific interest in exploring climate change in relation to minorityperspectives (IBPOC, LGBTQ2, Disability)

| Yes, I’m interested in exploringminority perspectives | No comment |

| 12% | 88% |

Graph 10: Applicants expressed specific interest in Indigenous perspectives on art and climate change

| Yes, I’m interested in learning aboutIndigenous perspectives | No comment |

| 15% | 85% |

Graph 11: Applicants who have already taken environmental action at some time

| Yes, I’ve already taken action | No comment |

| 99% | 1% |

Graph 12: Top reasons why applicants applied to Artist Brigade

| Reason | Approximate % |

| Use art to connect with nature | 31% |

| To build or join a community | 22% |

| To address climate anxiety and grief | 15 % |

| To be mentored | 6% |

| Learn how to connect with politicians | < 2% |

| Learn how to work with youth and climate | < 2% |

Graph 13: Applicant beliefs regarding the role of the artist in climate

| Mode | Approximate % |

| Mode 1: Greening the sector | 18% |

| Mode 2: Raising the profile | 43% |

| Mode 3: Invent new futures | 15% |

2. Recruitment: Applications Summary (Artist Brigade Participants)

Graph 1b: Career Stage

| Emerging | Mid-career | Established |

| 51% | 41% | 8% |

Graph 2b: Discipline

| Interdisciplinary | Fine Arts | Theatre | Film | Music | Design | Dance |

| 89% | 3% | 4% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 0.5% |

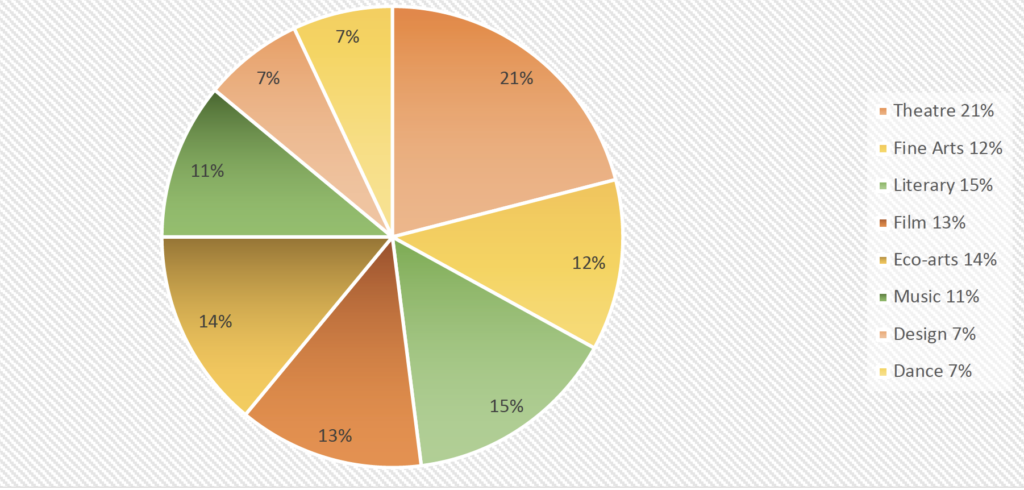

Graph 3b: Distribution of Interdisciplinary Artists

Graph 4b: Ethnicity

| White | Mixed | Chinese | S.Asian | W.Asian | LatinAmerican | Filipino | Korean | Indigenous | Black | Prefernot tosay | |

| ArtistBrigade % | 44% | 23% | 10% | 5% | 4% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 6% |

| GeneralPopulationBC % | 65.6% | NA | 11.2% | 9.6% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 3.5% | 1.5% | 7.7% | 1.3% | NA |

Graph 5b: Mixed Ethnicity Breakdown

Graph 6b: Indigenous Self-Identified

| Non-indigenous | Indigenous |

| 98% | 2% |

Graph 7b: Geography

| Lower Mainland | Vancouver Island+ Coast | Kootenay | Thompson-Okanagan | Other |

| 89% | 7% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

Graph 8b: Participants with international or regional lived experience of climate change

| Yes, I have diversity of livedexperience with climate change | No comment |

| 36% | 64% |

Graph 9b: Participants expressed specific interest in exploring climate change in relation to minorityperspectives in their applications (IBPOC, LGBTQ2, Disability)

| Yes, I’m interested in exploringminority perspectives | No comment |

| 16% | 84% |

Graph 10b: Participants expressed specific interest in Indigenous perspectives on art and climate change in their applications

| Yes, I’m interested in learning aboutIndigenous perspectives | No comment |

| 23% | 77% |

Graph 11b: Participants who have already taken environmental action at some time

| Yes, I’ve already taken action | No comment |

| 100% | 0% |

Graph 13b: Participant beliefs regarding the role of the artist in climate

| Mode | Approximate % |

| Mode 1: Greening the sector | 17% |

| Mode 2: Raising the profile | 43% |

| Mode 3: Invent new futures | 13% |

3. Feedback on Greenhouse – Survey summary (57 responses)

Graph 14: What did participants like about Greenhouse?

Graph 15: What did participants dislike about Greenhouse?

Graph 16: Did Greenhouse alter your level of climate anxiety/despair?

| Increase | Decrease | Same |

| 13% | 44% | 43% |

Graph 17: How did Greenhouse change your experience of climate anxiety/despair?

Graph 18: Having been part of Artist Brigade, what Mode best describes your role as an artist in the climate emergency?

Graph 19: Having been part of Artist Brigade, what other descriptions of your role in the climate emergency?

Graph 20: Do you have any plans to make a piece of climate-engaged art right now?

| Yes | Maybe | No | No response |

| 77% | 16% | 0 | 7% |

4. Field Trip Application- Survey Summary

Graph 21: Which field trip would you most like to attend?

| Trip 1: Forest inDanger | Trip 2: Knittingthe Past | Trip 3: Artist’sPart | Trip 4:SustainableLiving |

| 39% | 22% | 12% | 27% |

5. Field Trip Pitches – Pitches Summary

Graph 22: What modes of art projects were pitched for field trip 1: Forest in Danger? (12 pitches)

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Indigenous Led | |

| # of pitches | 0 | 4 | 9 | 0 |

Graph 23: What modes of art projects were pitched for field trip 2: Knitting Past and Future? (7 pitches)

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Indigenous Led | |

| # of pitches | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

Graph 24: What modes of art projects were pitched for field trip 3: The Artist’s Part? (7 pitches)

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Indigenous Led | |

| # of pitches | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

Graph 25: What modes of art projects were pitched for field trip 4: Sustainable Living? (10 pitches)

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Indigenous Led | |

| # of pitches | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

6. Post Artist Brigade Feedback – Survey Summary

Graph 26: What did you like about artists brigade? (25 responses to checklist)

Graph 27: What could be improved about Artist Brigade? (25 responses to checklist)

Graph 28: What did you like about the workshops? (12 responses)

Graph 29: What did you dislike about workshops? (5 responses)

Graph 30: Why didn’t you participate in workshops? (15 responses)

Graph 31: What did you like about field trip? (19 responses)

Graph 32: What did you dislike about field trip? (13 responses)

Graph 33: Why didn’t you attend field trip? (5 responses)

Graph 34: Feedback on pitches process (12 responses)

Graph 35: Did you like weekly emails? (24 responses)

Graph 36: Did Artist Brigade transform your artistic process? (24 responses)

Graph 37: How did Artist Brigade transform your artistic process? (24 responses)

Graph 38: Other feedback on Artist Brigade? (14 responses)

7. Commissioned Pitches 2022-23

Graph 39: What modes of art were pitched for 2022-2023 commissioned art? (34 applicants)

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Indigenous Led | |

| % of applicants | 2 | 9 | 21 | 1 |

Greenhouse Workshop Word Trees

Commissioned Artist Profiles

Mohammed Zaquot

Mohammed Zaquot identifies as an emerging artist who works in both literary and fine arts. In his application to the Artist Brigade, Mohammed explained that he grew up in a refugee camp in Palestine, an area that the United Nations as being an unlivable place by 2020 due to climate change, war, and pandemic. Now living in British Columbia, Mohammed aims to use the arts to collaborate with refugee youth to learn more about land and climate. In the Greenhouse video, Mohammed briefly tells his story about growing up in Palestine and his intention to work with asylum seekers. He attended the “Forest in Danger” field trip, which was his first choice. He didn’t make a pitch after the field trip, but he did present a pitch for the 2022-2023 cycle. His pitch focused on inviting asylum seekers to use arts to connect with natural world in BC, using poetry, storytelling, hands-on making, and public presentation. He will work with Runaway Moon Theatre’s Cathy Stubbington for whom he performed as a Blue Person in Song BirdForest. Mohammed conveyed his interest in collaborating with an Indigenous artist as part of this project as well. As of March 2023, Mohammed’s work is in development.

Wen Wen (Cherry )Lu

Wen Wen describes herself as an emerging artist who works in visual and installation arts. In her application to the Artist Brigade, Wen Wen explained she was born in Shanghai, at a time when there was little consideration for the environment and little access to green space. Upon immigrating to British Columbia, Wen Wen was amazed to have access to nature, and began immersing herself in forest, mountains, fields, and oceans. As Wen Wen learned more about colonialism and climate change, she recognized the complexities of accessing nature, and yearned to learn how to respectfully relate to land. Her artistic process engages with some of these ideas. Wen Wen attended field trip 1 and 3, and made a pitch after field trip 3 which was commissioned, “Come dream with me in the forest.” Wen Wen made a second pitch for the 2022-2023 call, and this Mode 3 pitch builds upon her first. The new piece will be an animation developed through community workshops with Chinese immigrants, and it will focus on how language draws out ancient values around environmental stewardship and identity.

Matthew Ariaratnam

Matthew identifies as an emerging and mid-career, interdisciplinary artist of mixed, South Asian descent. In his application to the Artist Brigade, Matthew explains that climate change fills him with despair and curiosity. Matthew takes interest in sound pollution and deep listening, and wonders if listening to the environment can encourage publics to conserve nature. Matthew did not take part in a field trip nor field trip pitch. He made a pitch for the 2022-2023 cycle, which focuses on creating a version of his score entitled “Tones to Melt and Heal Hardened Heart.” For this score, he aims to have 100 recorded tones that would be put together in a tonal tapestry to be diffused in different public spaces that could be accessed by bicycle. The tones would be created with collaborating artists and would invite listeners into a guided meditation. Matthew’s goal is to create softness and gentleness, in a psychic-emotional way, and as a demonstration of what happens when many people come together. Matthew is currently developing partnerships with community and arts organizations to help present the work to publics.

Sunkosi (Suna) Galay-Tamang

Sunkosi identifies as a mid-career, interdisciplinary artist of Indigenous and South Asian descent. In their application to the Artist Brigade, Sunkosi conveys their interest in exploring the climate issue outside of science, and in relation to restoring balance with nature. Sunkosi attended Field Trip 2 and made a pitch following the field trip that focused on teaching participants about weaving corn husks and hide tanning. Sunkosi also intended on developing a Zine with the collaborating artist. This piece was commissioned and became “Remembering Mothertongue”. Sunkosi has pitched a second project as part of the 2022-2023 cycle, that focused on hosting a buffalo hide camp in Strathcona Park.

Kimberly Skye Richards

Kimberly identifies as a White, emerging, interdisciplinary/theatre artist. In their application to the Artist Brigade, Kimberly explains that they grew up in Alberta where they witnessed the violent destruction of land by companies who drill for oil. Kimberly uses the arts to perceive and reimagine relationships to oil and energy, and they were already involved in making and presenting climate art before Greenhouse. Kimberly made a pitch in the first funding cycle and attended field trip 2 and Corey Matthew’s climate grief circles. Kimberly’s pitch was commissioned and is entitled Instructions for grieving this change/ instructions for changing this grief.

Kelly McInnes

Kelly identifies as a White, mid-career, dance, eco, and interdisciplinary artist. In their application to the Artist Brigade, Kelly conveys that they grew up on in Northern British Columbia, and experience climate emergency as a wound that will never heal. Kelly studied craniosacral therapy and connects their artistic practice to trauma-informed healing. Before Greenhouse, they already looked to make art that is not about sharing information but rather about processing complex emotions in an embodied way. Kelly attended field trip 1 and made a pitch for the 2022-2023 cycle. Their pitch, “Late Stage Remedy” is a 1-hour improvised, dance meditation that would take place at Jericho Beach in Vancouver. The slower paced movement of the dance draws witness’ attention to the natural world, allowing for more introspection, creativity, and regulation.

Future Interview Questions for Case Studies

- What led you to become an artist?

- What kind of work were you making before the Artist Brigade?

- How did you feel about climate change before Artist Brigade?

- Why did you decided to join the Artist Brigade?

- What do you like best about the Artist Brigade?

- In what ways has your artistic process changed due to your participation in Artist Brigade?

- How has the Artist Brigade process changed your art making?

- What are your plans for art making in the future?

- How are you feeling about climate change now?

Future Survey Questions

- On a scale from 1-5 how focused is your artwork on the climate crisis?

- Not motivated; it’s not my issue

- Really concerned but not making climate art due to my anxiety

- I’ve made one climate artwork

- I’ve made a few climate artworks

- Climate artwork is my entire practice

- If you are an artist that works in multiple disciplines, what is your principal discipline?

- Theatre

- literary

- Film

- music

- dance

- design

- Eco-arts

- Fine arts

- Other

- Select your top 3 reasons for applying to the Artist Brigade:

- Wanting to make art

- Build community

- Address climate anxiety

- To be mentored

- To learn about working with youth

- To learn how to connect with politicians

- To learn about new research

- To learn how to make by practice more environmentally friendly

- Other

Quotes and Metaphors

“For most of my adult life I feel I have engaged with the climate issue in the way that many people like me (white, privileged, comfortable) have done: I’m moderately concerned about climate change, I recycle, I bike a lot and don’t own a car, I think hard (but not always too hard) about my consumer choices, that kind of thing. […] What I want to work on and learn now is 1) how to have hope, 2) actual concrete actions to take that can influence the bigger picture, 3) how to make art as a celebration that speaks to a utopian future, in which we’ve turned things around, rather thanmaking art as a warning, which I find just shuts me down.” Greenhouse Application Art as the Trojan Horse for climate change. Don’t make a shitty looking horse. – Artist Brigade participant in Maggs’workshop with Maggs (Not a direct quote, just a summary of conversation)

“After Greenhouse, it is clear to me that art, imagination, is a better agent for change than information and facts. Still, as an artist I must stay informed and work from a place of awareness of the climate urgency. Picasso said that art is a lie that tells the truth. There is not one role for the artist, but for me it means to invent a story, an image, a possibility that makes change a desirable destination.” Post-Greenhouse Survey

“So what we’re here to do today, is just to connect with our grief, with our legitimate loss, our feelings of displacement. […] Our experience of losing everything around us, which is a terrifying and horrifying prospect. It’s something that we’re watching happening year in and year out, and it’s a soul crushing endeavor. […] I think that we collectively have been denied access to our birthright, which is to know how to grieve. Know how to build community through grief, to feel loss, in a true way. In a way that honors the love of the places that are being destroyed. Thathonors the anger that comes with that love. That speaks to the depth of love because that is what grief is, it’s love, it’s just love”. Corey Matthews, “Climate Grief”, minute 47:30

“I want you to think of a time of transformation in your life, so like an a-ha moment. So maybe a revelation that made you see something differently. Maybe it was a person or an experience that was a catalyst for some illumination or a way of seeing something differently. It doesn’t have to be big, it can be like the moment you found out where babiescome from. It can be anything.

Think about what state you were in that allowed you to have that moment of transformation or illumination. What state were you in? That allowed you to have that insight, or change of mind or change of heart”. Sherry Yano,“ENGO Problems for Artists”, minute 24:57

“I’m going to introduce this potential process. […] We’re doing a sneak peek through it. But we are starting here at the introduction, systems thinking, thinking about thinking. Today is about the problem framing, getting to the root cause of what are the issues associated with climate change. Tomorrow we will get into a vision, if we were wildly successful, what would it look like? How do we reimagine this future world? And from that, we’re going to explore different types of solutions, and how we diverge and think about a lot of solutions? And ultimately converge, to have some key solutions that we might want to think about. In the social innovation process, the importance of designs and prototypes, and bringing your idea to life, and sharing and testing it, and getting some feedback on your solution. And then ultimately, when you’ve come this far, it’s designing an impact for how your solution can move forward.” Tara Moreau, “All Hands on Deck: ClimateCrisis”, minute 5:19

“So to try to avoid that and yet still walk the arts into a more emboldened relationship with a social context, what I’ve tried to do, is identify a kind of composite nature of artistic process. To insist that before art is a power of expression, it is also equally a necessary power of attention. That art is the ability to pay attention to the world in terms of the aesthetic, in terms of form and pattern, rhythm and harmony, shapes, imagery, and pitch. All the materials that an artist works with are a way of paying attention to the world. A way of inquiry into the world. And so I’ve been using this image of the butterfly. It’s very easy to be caught up with a sense of art as the expressive butterfly but if we miss asense of art in that attentive caterpillar, then we’re not going to get the thing that we’re really after when we are trying to engage with art inside the processes. The caterpillar is not as flashy, we often don’t notice it, but if it’s not present and active inside these processes, then we’re not going to get the results that we typically expect from the arts.”

David Maggs, “Role of the Artist: Art and the World After This”, minute 21:00

“You have to activate peoples’ heart, because that is the warmth that melts anxiety, fear, those kinds of blockages, that kind of hollowness, that brings us out of contraction into a more open state. […] Then people mobilize.” Kendra Fanconi, “Artists at Work in the Climate Movement”, minute 5:40

“I want to make love stories. I want people to connect and fall in love with places because what you love you’ll protect” Kendra Fanconi, “Artists at Work in the Climate Movement”, minute 13:40

“The work of reauthoring the world is this work of helping us understand what is the world that lies on the other side of the carbon transition. The reason why we need to have that is what the David Suzuki Foundation calls “beach thinking”. If you’re going to go to Hornby Island for your beach holiday, in the summer, you might have a two-sailing wait, and maybe one of the kids throws up in the car, and all the sandwiches have sand in them. But you don’t turn around and leave the ferry line or go home. You’re trying to get to the beach! And that vision of the beach gets youthrough all of the sacrifices that you have to get through in order to get to the beach. But here we are, in this climate crisis, we’re getting all tied up in the sacrifices of getting there because we don’t know what the beach is. And this isthe work of art, this is the work of artists, to help us imagine that future, that beach.” Kendra Fanconi, “Artists at Work in the Climate Movement”, minute 48:25

Orientation Evaluation Framework

Goal: Support artists in making work that provides inventive and revolutionary answers to the climate crisis.

Objective 1: Provide artists with a transformative, embodied experience that changes their art making.

Method:

- Introduce artists to a technique or creative process

- Bring artists to a site

- Offer artists a performance Measurement:

- # of artists introduced to new technique or process?

- # of artists brought to a site?

- # of artists witness performance?

- Survey for feedback on technique, site or performance?

Objective 2: Connect artists to a community of climate artists.

Method:

- Send email communications to group of artists

- Provide opportunities for artists to meet

- Provide opportunities for artists to collaborate Measurement:

- # of emails opened?

- # of meetings held

- # of collaborations

- Survey for open feedback on emails, meetings and collaborations?

Objective 3: Help artists feel empowered by showing that art is important to climate activism.

Method:

- Pay artists for their pitches

- Commission artwork

- Share stories about art being important Measurement:

- # of pitches presented

- # of commissions

- Survey for open feedback on feeling empowered?

Objective 4: Enable the work of equity seeking artists.

Method:

- Recruit equity seeking artists to Artist Brigade

- Equity seeking facilitators lead workshops

- Commission equity seeking artists

- Pay equity seeking artists for involvement in Artist Brigade

- Provide opportunities to provide feedback in safe context

Measurement:

- # of participants, facilitators, commissions

- Survey for open feedback

Objective 5: Support Indigenous sovereignty over Indigenous culture.

Method:

- Pay Indigenous artists for involvement in Artist Brigade

- Continue developing respectful relationships with Indigenous artists and communities

Measurement:

- # of participants, facilitators, commissions

- Survey for open feedback

The Artists of the ONLY ANIMAL’S ARTIST BRIGADE:

* includes names of artists who consented to being in the list

- Alen Dominguez

- Alex Masse

- Alyssa Martens

- Anaïs Pellin

- Carolyn Nakagawa

- Cathy Stubington

- Chantal Dobles Gering

- Charles Douglas

- Christian Ching

- Cláudio Cruz

- Conor Wylie

- David Bloom

- Derek Chan

- Diemm McLennan

- Evan Medd

- Gilles Cyrenne

- Hannah Abbott

- Howard Dai

- Jackson Wai

- Chung Tse

- Janey Chang

- Jenna Masuhara

- Jennifer Mascall

- Jillian Read

- Joanna Liang

- Judith Atkinson

- Juno Avila-Clark

- Kamila Sediego

- Kat Savard

- Katherine Binns

- Kelly McInnes

- Kim Richards

- Kris Fleerackers

- Kyla Hewson

- Lara Aysal

- Laura Fukumoto

- Leah Day

- Leanne Dunic

- Lisa Baran

- M. Simon Levin

- Maki Yi

- Maria Angélica Guerrero

- Matthew Ariaratnam

- Meesh QX

- Michael Dove

- Minah Lee

- Mohammed Zaqout

- Monica Gewurz

- Nita Bowerman

- Olivia Etey

- Panthea Vatandoost

- Paolo Davanzo

- Pierre Leichner

- Rachel Rozanski

- Robyn Jacob

- Sammie Gough

- Sara Ross

- Sarah Higgins

- Sarah Ronald

- Sepehr Samimi

- Shel Neufeld

- Shreyasi Das

- Sidi Chen

- Steve Tornes

- Suna Galay

- Susan Jessop

- Sylvia Grace Borda

- Therese Champagne

- Thomas Evdokimoff

- Thule van den Dam

- Trish Malcomess

- Wen Wen (Cherry) Lu

- Wryly Andherson

Appendix 1: IRRESISTIBLE WORLDS INTERVIEW REPORT

On 2 May 2023, Dr. Alana Gerecke facilitated a Zoom conversation between three climate art leaders: Chantal Bilodeau, Andre Forsythe, and Kendra Fanconi. The Zoom call was recorded and has been made available for future viewing. In what follows, Gerecke has gathered some of the main themes and key quotations that emerged during this interview.

Chantal Bilodeau is a Montreal-born, New York-based playwright whose work focuses on the intersection of storytelling and the climate crisis, and the founding artistic director of the Arts & Climate Initiative. She is currently working on a series of eight plays that look at the social and environmental changes taking place in the eight Arctic states. In 2019, she was named one of “8 Trailblazers Who Are Changing the Climate Conversation” by Audubon Magazine. http://www.climatechangetheatreaction.com/ & https://artsandclimate.org/ & https://www.cbilodeau.com/

Andre Forsythe is the founder of Canadian Climate Challenge and Project Lead of The School for Climate. Building on 10+ years of sustainable fashion experience, Andre’s current focus is on increasing accessibility to climate solutions and environmental justice awareness and mobilization. Through art, activism, technology, partnership, community organizing, membership in the National Anti-Environmental Racism Coalition, and as a steering committee member of the Toronto Climate Action Network, Andre puts his energy anywhere he can to convey a sustainable, inclusive, and just Canada. https://climatechallenge.ca/ & https://www.schoolforclimate.com/

Kendra Fanconi is the outgoing Artistic Director of The Only Animal, a seventeen-year old company that is uniquely dedicated to theatre that springs from a deep engagement with place. As a director, playwright, and producer she has made over 30 site-specific plays including theatre of snow and ice, sand, in trees, on mountains, and on active waterways. Favourite projects include tinkers based on the Pulitzer-Prize winning novel by Paul Harding, performed at Crystal Creek on the Sunshine Coast, and NiX, theatre of snow and ice that was featured at Calgary’s Enbridge play Rites Festival and the 2010 Cultural Olympiad. Kendra has taught her unique creation style of design-based dramaturgy at University of British Columbia and Playwrights Theatre Centre. She lives in Roberts Creek and is a farmer, forager, and mother of two kids who are real characters. www.theonlyanimal.com

Based in Vancouver, on the unceded and ancestral territories of the Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh, xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm, səlilwətaɬ nations, Alana Gerecke (PhD) is an independent scholar, artist, and post-secondary educator of mixed European descent. Her research on the spatial politics of site- specific performance and urban choreographies feeds her dancing, performance making, writing, teaching, and parenting. www.alanagerecke.com

- After a welcome and a land acknowledgement, Gerecke invites each artist to offer a self- articulation of theirpractice, as well as a land acknowledgement.

- Each artist is invited to tell a story about what brought them toward a climate orientation in their artistic practice.

- Each is asked to articulate their understanding of the unique role, value, and capacity of art to stimulate movement toward climate justice.

- Each is asked how they create and/or curate work in relation to climate grief, climate anxiety, climate realism, and/or climate hope. The underpinning question is: what stories do we need to hear in this climate moment?

- Recognizing that we are learning collectively about best practices for making climate- oriented art, for working in/with community, and for reaching across sectors and disciplines, each artist is invited to share a lesson they have learned in their practice— maybe a lesson they’ve learned the hard way—something they carry forward that will shape their future choices.

- Acknowledging the complexity and overwhelm that often attends climate work, each artist is invited to share ideas about how to prepare, support, and guide artists to harness their unique power to contribute to climate action.

THEMES THAT EMERGED DURING THE INTERVIEW:

Building narratives, “broken narratives”

A central question threads through this conversation: which stories do we need to hear in this climate moment? While artistic practice serves the important role of carving out space for climate grief in community—and for a recognition that grief is an extension of love (Bilodeau and Fanconi)—the artists also articulate the need to balance the ubiquitous, mass-media narrative of climate “failures” with narratives of climate successes (Bilodeau). Each artist echoes this sentiment, emphasizing the need to identify and amplify hopeful narratives as we work toward climate solutions. Artistic practice has the capacity to “change a broken narrative and start telling a new story” (Forsythe), to balance and personalize the stories we hear, and to celebrate “what is working” (Bilodeau) in order to move us into narratives that can sustain us, and that we can sustain.

There are overlaps in each artist’s take on the unique potential of art to contribute to climate solutions. Bilodeau refers to art as a “seed” that can move people toward climate action and climate activism: “art is there to open people’s hearts” (Bilodeau). Forsythe emphasizes the potential of art to empower communities to come together to collectively imagine the systems and relationships they want to manifest, starting with an affirmation of what they love about their community. Fanconi builds on Forsythe’s interest in relationships, insisting that—with their insights into relationships of proximity, distance, and density—artists are “well positioned to go into these very difficult conversations.” Fanconi goes on to describe the power of “magic” and the imagination in artistic expression to open people up to challenging content, making reference to how a “flying piano” in a past performance melted her resistance and drew her to engage deeply with aproduction that centered on particularly difficult subject matter.

Scaled and sustained action

Toggling between the big, aspirational, world-making goals that drive climate art, and the small, local, “skin-in-the-game” opportunities to engage folks on the climate crisis (Forsythe), there is a recognition of the need to “meet people where they are” (Forsythe). The artists overlap in their efforts to create sustained engagement on climate issues over time—in addition to generating energy toward climate action in one-off events. Each practitioner offers examples of locally relevant and approachable modes of practice that counter the polarizing “all or nothing” thinking that can attend the climate crisis (Bilodeau). Fanconi refers to Harvard scholar Erica Chenoweth’s theory of change and the importance of mobilizing only 3.5% of a given population in order to effect change. Fanconi looks at estimates of Canadian art audiences and frames this 3.5% population reach as a resolutely achievable goal.

Collectivity and climate action

The importance of community and connectivity in facing the current climate challenges comes through in each artist’s account of their practice. Forsythe explains that he was first drawn to climate work because he felt that the issue “couldn’t be othered”; that is, as an issue relevant to all of us, addressing the climate crisis can “bring us together” (Forsythe). Fanconi insists on the importance of collaboration and collective action in addressing the climate crisis, pointing to theatre as a collective art form that ensures that participants draw strength from their connection. And Bilodeau draws out the importance of “be[ing] in a room with other people who have the same concerns.” Each emphasizes art as a medium of connectivity with the capacity to bring folks together as a community or collective. At the same time, both Forsythe and Bilodeau stress the uneven distribution of climate crisis impacts, and they underscore the different capacities and needs of communities based on their proximity to the “frontlines” of the crisis.

Exponential growth and mushrooms

Fanconi addresses the need for the exponential growth of climate art and activism—to parallel the exponential growth of the climate crisis—by developing Bilodeau’s suggestion that art is a seed that can be planted to move people toward action. Reaching outside of her Zoom screen, Fanconi picks up a morel mushroom from her kitchen table and shows it to the group. As she holds the mushroom, she leads us back to the conversation about seeds: “You can’t even see the spores of mushrooms. They’re so small, they just travel in the air and then—lo and behold—they become this!” Fanconi frames exponential growth as “the most natural thing in the world,” insisting that, like morels, a “revolution of artists” can grow in an exponential way.

KEY QUOTATIONS:

“You can’t other [the climate crisis], because it relates to us all in in some way.” (Forsythe)

“I think at this point one of the most important things that art can do is create space for grieving. Because a lot of the losses we’re experiencing are not, we don’t really have public spaces to talk about them. And then help transformthese feelings into empowerment and action. We are inundated with negative stories about the climate, stories of failure, essentially. Climate disasters, failure of policy, failure of corporations to do the right thing, failure of (and it’s debatable whether this is true or not), but failure of individuals to do the right thing. I think that it’s very important to change that conversation. Otherwise, it leads to some of what we’re experiencing, which is either apathy or despair.” (Bilodeau)

“Another thing I would mention is this all or nothing thinking: either we’re going make it, or we’re not going make it. Which is also not helpful because once you slip into the side of ‘oh, we’re not going make it,’ then you can just stop, right? Because you feel like your contribution is not necessary or useful. And the truth is that it’s going to be somewhere in between, and that’s a very difficult place to live in because it’s uncertain. […] It’s about working towards something that’s going to be a compromise, that’s not going to be perfect—and continue working towards it anyway, knowing that we are having an impact even if the golden goal is not achieved.” (Bilodeau)

“When I look at the absolute essence of what has happened to create the climate crisis, I think of a phrase that was in what Andre’s landed acknowledgement about the ‘broken narrative.’ It’s about connection and disconnection for me, at the very heart of it. And I find art and theatre and all kinds of artistic practice to connect us. To connect us with what? Well, to connect us with each other, with our truths, with ourselves, with the things that deeply, deeply make us happy— which are probably not what we’re buying on Amazon. It is things like community and belonging and home and love, none of which can be bought on Amazon. I believe art is completely at home in all of those stories. How do we create belonging—love and connection—with an ecosystem, with a species, with a non-human species, with each other, with our own species? When I look at the absolute essence of the role of the artist, I think that our role is to connect.” (Fanconi).

“I also reflect on the work of Erica Chenoweth and her theory of change. She’s a Harvard researcher who looked at a history of nonviolent revolutions going back centuries, and asked: what is it that has created change? She says when you mobilize 3.5% of population—so in Canada, that’s about. 1.5 million people—when you mobilize them, that has never failed to create change. […] Well, those people are in our audiences! They’re in our theatres, they’re watching our films, they’re going to our galleries, they’re in the street, seeing the work that happens there.” (Fanconi).

“What does your community mean to you? How do you see your community going forward? […] What do I love about this place? And building that connection to climate from there. That’s where we find that people step up and we see leadership roles start to emerge there, where people feel more comfortable in that space—because it’s close enough. They have skin in the game because it’s their neighbourhood, their community—they want to be engaged, and they can see… It’s a scale where they can see changes” (Forsythe).

“No one is going to feel like they can do this alone, so we’re really trying to focus on the level of engagement where people feel that we can build that autonomy and build that empowerment” (Forsythe).

“One thing that was very important, and I have had this comment from audiences before, was to be in a room with other people who have the same concerns” (Bilodeau)